#BlackLivesMatter: Guide to 6 Black Poets Who Have Given Me Strength

Written by Yunqin Wang

In one of the essays of Joseph Brodsky, he declared that at certain periods of history, it might be only poetry that is capable of dealing with reality by condensing it into something graspable, something that otherwise couldn't be retained by the mind. In a moment like this, when sounds of sirens, voices for justice, cries of victims drum in our ears all at once, I believe alongside donating and speaking up, another thing we could do is to understand. To understand what is happening and the people being involved. We do not want to be suffocated together in this air of bias, violence and intolerance. And these poets, clinging to their pens and sheaves of paper all along, have been paving a long road for this understanding to happen.

In this article, I’m sharing with you some of the black poets who have moved me deeply. Their influence over not just the literary realm but also the entire human history has proclaimed over and over: black lives matter.

Lucille

Clifton

“won’t you celebrate with me” by Lucille Clifton is one of the earliest poems I have ever read in my life, and it then became a poem that supported me during some of my most difficult times. Clifton, who has experienced segregation and racism firsthand, has offered me with this poem a guide to self-understanding.

Born in Depew, New York, Lucille Clifton was the first author to have two books of poetry chosen as finalists for the Pulitzer Prize and the winner of Ruth Lilly Poetry Prize, whose judges marvelled at the looming humaneness and moral quality in her works. Many of her poems, including “won’t you celebrate with me” were written in the 1960s. It was a time when the civil rights movement awakened a new sense of self-awareness of African Americans. As part of this generation of whom had experienced both an historical exile from Africa and a metaphorical exile from the so-called American Dream, Clifton has always sought in her poetry to position herself and her people in relation to the world. Her works emphasized endurance and strength through adversity.

In this short poem “won’t you celebrate with me”, as the narration goes, the speaker gathers more and more strength from her own experience, more confidence from her ability to stand alone. It investigates reasons for the faltering sense of identity and then overcomes it, thus giving me strength too.

won't you celebrate with me

what i have shaped into

a kind of life? i had no model.

born in babylon

both nonwhite and woman

what did i see to be except myself?

i made it up

here on this bridge between

starshine and clay,

my one hand holding tight

my other hand; come celebrate

with me that everyday

something has tried to kill me

and has failed.

Gwendolyn Brooks

I was introduced to Gwendolyn Brooks in my first creative writing class in college. The poem we read was “The Sundays of Satin-Legs Smith”, the longest poem in Brooks’ first collection, “A Street in Bronzeville”. I was immediately attracted to the poet’s elaborative language which weaves the character’s inner-self and the awareness of the outside world so well -- there is irony, and also beauty. That is Gwendolyn Brooks, she is always clear about who the people she wrote were and what it meant to write about them. And for most of her works, even though her creative style went through different phrases--from tighter to more loosened with less dense allusions--her subject matter has remained unchanged: she looks at the black people who lived in the kitchenette apartments of Bronzille.

One of the most highly regarded poets of 20th-century American poetry, Brooks was the first Black author to win the Pulitzer Prize, and also the first Black woman to be assigned the poetry consultant to the Library of Congress. Distilling a modernist style through the unique sounds and shapes of a variety of African-American forms and idioms, her works, especially those from the 1960s and later, often display a political consciousness too. I am moved by the unambiguous race pride penetrating through her words which, after so many years, still ring true to the complex poetic details of black people’s lives.

This poem below is from the collection, “A Street in Bronzeville”. Starting with the pronoun “we”, the poem immediately brings out a crowded yet lonely voice of this community living in these close quarters.

kitchenette building

We are things of dry hours and the involuntary plan,

Grayed in, and gray. “Dream” makes a giddy sound, not strong

Like “rent,” “feeding a wife,” “satisfying a man.”

But could a dream send up through onion fumes

Its white and violet, fight with fried potatoes

And yesterday’s garbage ripening in the hall,

Flutter, or sing an aria down these rooms

Even if we were willing to let it in,

Had time to warm it, keep it very clean,

Anticipate a message, let it begin?

We wonder. But not well! not for a minute!

Since Number Five is out of the bathroom now,

We think of lukewarm water, hope to get in it.

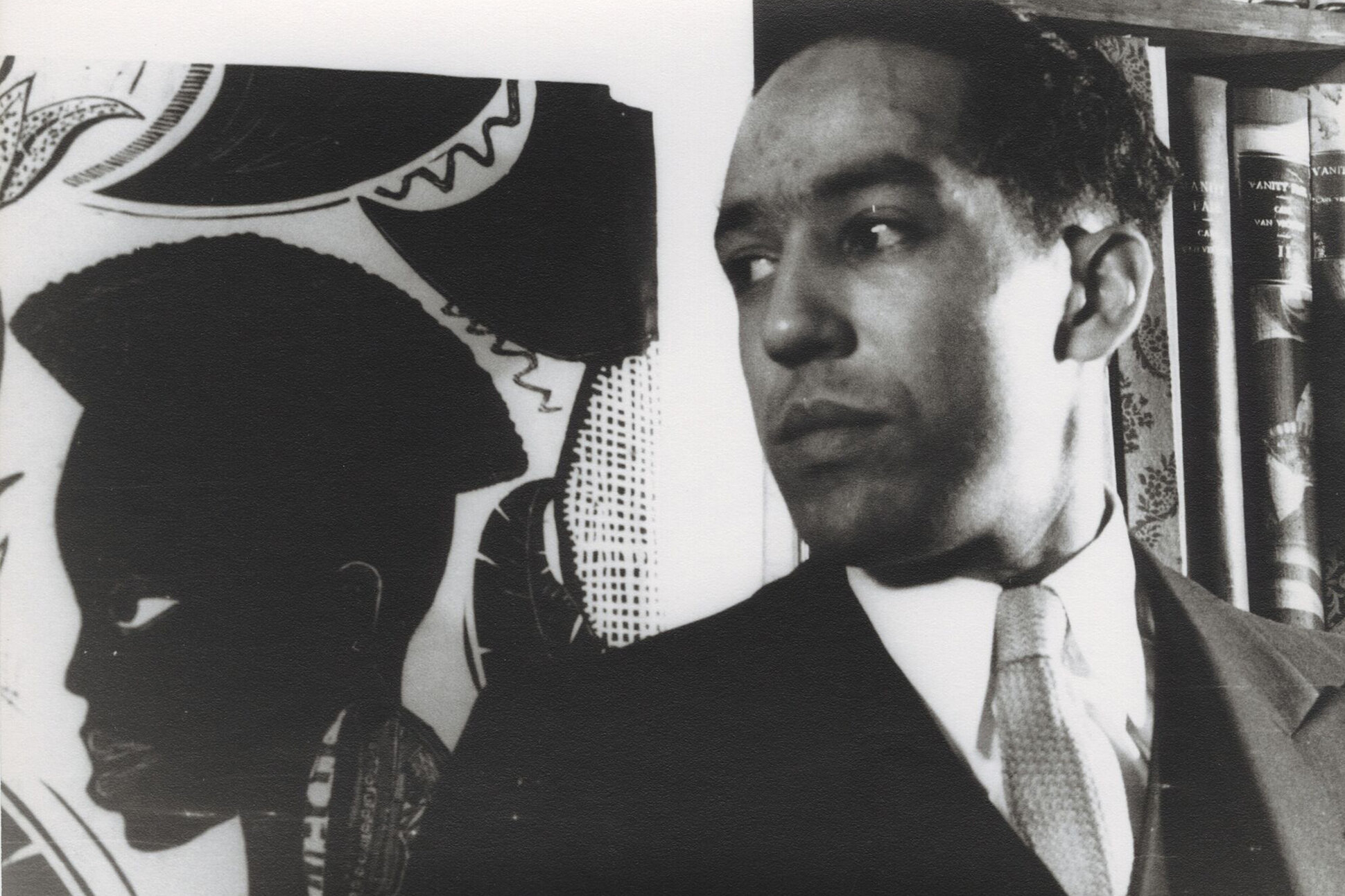

Langston Hughes

Langston Hughes, has been one of the early and enduring influences of Brooks. The conversational and syncopated rhythms, people and personalities, as well as urban settings in Brooks’ works to some degrees owe to Hughes’ influences. And Langston Hughes, a major poet and a central figure of the Harlem Renaissance--the flowering of black intellectual, literary, and artistic life that took place in the 1920s in a number of American cities--could be regarded almost as influential an anthologist as he was a poet. Portraying the joys and hardships of working-class black lives yet avoiding both sentimental idealization and negative stereotypes, Hughes’ works have for several generations of readers helped form a sense of an American poetics and the possibilities of African American literature. Through his words, we not only witness moments of race-pride, but also feel a strong sense of urgency, an urgent revelation and belief. Helen Vendler has once commented that perhaps, in this man’s hurried life, “he may have believed the cause was so urgent that it did not leave him the time for that digestion of thought into style that alone allows poetically successful representation of belief.”

Harlem Renaissance

In this piece below, Hughes, adopting a Whitman-style voice performed yet what Whitman could not achieve: he imagines a truly equal place at the table for “the darker brother.” It sings to me how beautiful the black experience is.

I, Too

I, too, sing America.

I am the darker brother.

They send me to eat in the kitchen

When company comes,

But I laugh,

And eat well,

And grow strong.

Tomorrow,

I’ll be at the table

When company comes.

Nobody’ll dare

Say to me,

“Eat in the kitchen,”

Then.

Besides,

They’ll see how beautiful I am

And be ashamed—

I, too, am America.

Maya Angelou

I believe most of us are familiar with Maya Angelou, but she is indeed the figure who should be brought up again at this time. She had a broad and distinguished career not only inside but also outside the literary realm. She is a poet, memoirist, and civil rights activist, working with Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X. She also worked in entertainment, as a singer, a dancer, an actor, and a director. Inspired by her own life and work, also with a firm root in African American history, the poetry of Maya Angelou bears both deep personal connections and the strength to bring out hopes, calling us to overcome any kinds of oppressions. The power of rhythm in Angelou’s verse also indicates her belief that life struggles could be overcome through rhymes and our voices. When she was eight, she was raped by her mother’s boyfriend who was killed shortly after. She thought her voice had killed the man and remained mute for five years, but developed a love for language. After all, she knows the great force of both oppression and voice, both silence and words.

Over the course of a career spanning the 1960s to her death in 2014, Angelou captured, provoked, inspired, and ultimately transformed American people and culture. By 1975, Carol E. Neubauer in Southern Women Writers: The New Generation remarked that Angelou should be recognized “as a spokesperson for… all people who are committed to raising the moral standards of living in the United States.” The poem below, written at the time of Black Arts Movement, is indeed calling every one of us in this society to rise, and live above the society.

Still I Rise

You may write me down in history

With your bitter, twisted lies,

You may trod me in the very dirt

But still, like dust, I'll rise.

Does my sassiness upset you?

Why are you beset with gloom?

’Cause I walk like I've got oil wells

Pumping in my living room.

Just like moons and like suns,

With the certainty of tides,

Just like hopes springing high,

Still I'll rise.

Did you want to see me broken?

Bowed head and lowered eyes?

Shoulders falling down like teardrops,

Weakened by my soulful cries?

Does my haughtiness offend you?

Don't you take it awful hard

’Cause I laugh like I've got gold mines

Diggin’ in my own backyard.

You may shoot me with your words,

You may cut me with your eyes,

You may kill me with your hatefulness,

But still, like air, I’ll rise.

Does my sexiness upset you?

Does it come as a surprise

That I dance like I've got diamonds

At the meeting of my thighs?

Out of the huts of history’s shame

I rise

Up from a past that’s rooted in pain

I rise

I'm a black ocean, leaping and wide,

Welling and swelling I bear in the tide.

Leaving behind nights of terror and fear

I rise

Into a daybreak that’s wondrously clear

I rise

Bringing the gifts that my ancestors gave,

I am the dream and the hope of the slave.

I rise

I rise

I rise.

Yusef

Komunyakaa

Last night, I put down the poetry collection Dien Cai Dau by Yusef Komunyakaa, feeling like I just had a long dream. It is a collection of poems on the poet’s experience as a soldier at the Vietnam War. Loss, struggle, fear, relations between black and white soldiers, humanity of the enemy… All kinds of emotions flow in this book, in between the harrowing lines.

On April 29, 1947, Yusef Komunyakaa was born in Bogalusa, Louisiana where he was raised during the beginning of the Civil Rights movement. From 1969 to 1970, he served in Vietnam as a correspondent and managing editor for the military newspaper Southern Cross, work that earned him a Bronze Star. Yet it was only in 1984, 14 years after he returned home, did he start to reflect on his experience in the war fields, and we thus have in hand the collection Dien Cai Dau, which means “crazy” in Vietnamnese. I think there must be certain intersections between how Komunyakka in his book reminds us of the struggles of those suffered, mistreated, even forgotten in the war and how today in the Black Lives Matter movements people once again actively start to voice out, listen, empathize. Komunyakka recounted the war experience in a distant yet almost ghostly voice. He is here dealing with some of the most complex moral issues, writing about the most harrowing ugly subjects of the American life, and yet, as the poet Toi Derricotte remarks, his voice, whether it embodies the specific experiences of a black man, a soldier in Vietnam, or a child in Bogalusa, is universal. And through this African American veteran, I have learned, deeply, what it is to be human.

Vietnam Veterans Memorial Wall

“Facing it” is the ending poem of the collection, though one of the first poems Komunyakka started out to write about the war 14 years later. Standing before the Vietnam Wall, he confronts his feeling for that history. And while reading I think, we should never turn our nation into a place which doesn’t recognize its own soldiers.

Facing it

My black face fades,

hiding inside the black granite.

I said I wouldn't

dammit: No tears.

I'm stone. I'm flesh.

My clouded reflection eyes me

like a bird of prey, the profile of night

slanted against morning. I turn

this way—the stone lets me go.

I turn that way—I'm inside

the Vietnam Veterans Memorial

again, depending on the light

to make a difference.

I go down the 58,022 names,

half-expecting to find

my own in letters like smoke.

I touch the name Andrew Johnson;

I see the booby trap's white flash.

Names shimmer on a woman's blouse

but when she walks away

the names stay on the wall.

Brushstrokes flash, a red bird's

wings cutting across my stare.

The sky. A plane in the sky.

A white vet's image floats

closer to me, then his pale eyes

look through mine. I'm a window.

He's lost his right arm

inside the stone. In the black mirror

a woman’s trying to erase names:

No, she's brushing a boy's hair.

June Jordan

In an episode of the “Poetry Off the Shelf” podcast, the host tried to introduce June Jordan but failed to categorize her. He said, “But let’s try. [She is] An African-American bisexual political activist, writer, poet, and teacher. But if you try to look at her through that lens, you will not see all of her.” Toni Morrison, on June Jordan’s career, remarked, "I am talking about a span of forty years of tireless activism coupled with and fueled by flawless art." Back in the 1960s, Jordan was one of the first writers to validate African American vernacular. And I wonder, what would Jordan, who had committed full heartedly to human rights and political activism throughout her life, make of the incidents we are facing today.

Born in Harlem in 1936 to Jamaican immigrant parents, she is a poet who was fiercely connected to and living in this world. She was so conscious and aware of what was going on politically, and more importantly, had the ability to bring that out into her work. We are constantly challenged by her words, being pulled out to confront this world. In a radio interview before her death, Jordan was asked about her role as a poet in the society. Here is part of the answer, “...the task of a poet of color, a black poet, as a people hated and despised, is to rally the spirit of your folks…I have to get myself together and figure out an angle, a perspective, that is an offering, that other folks can use to pick themselves up, to rally and to continue or, even better, to jump higher, to reach more extensively in solidarity with even more varieties of people to accomplish something. I feel that it’s a spirit task.”

While Jordan has left us physically, the power of her work stays real, transformative, transcending time. To end this article, I will include one of her last poems before cancer took her away. Jordan asks over and over In this poem, “what’s anyone of us to do / about what’s done” and answers through her action both inside and outside the poem. She is sending the message that the effort to do it, regardless of the degree of restoration, is hard but necessary like a laundry, and beautiful. This spirit of bettering the world through art and activism, let us pass it on.

It’s Hard to Keep a Clean Shirt Clean

Poem for Sriram Shamasunder

And All of Poetry for the People

It’s a sunlit morning

with jasmine blooming

easily

and a drove of robin redbreasts

diving into the ivy covering

what used to be

a backyard fence

or doves shoving aside

the birch tree leaves

when

a young man walks among

the flowers

to my doorway

where he knocks

then stands still

brilliant in a clean white shirt

He lifts a soft fist

to that door

and knocks again

He’s come to say this

was or that

was

not

and what’s

anyone of us to do

about what’s done

what’s past

but prickling salt to sting

our eyes

What’s anyone of us to do

about what’s done

And 7-month-old Bingo

puppy leaps

and hits

that clean white shirt

with muddy paw

prints here

and here and there

And what’s anyone of us to do

about what’s done

I say I’ll wash the shirt

no problem

two times through

the delicate blue cycle

of an old machine

the shirt spins in the soapy

suds and spins in rinse

and spins

and spins out dry

not clean

still marked by accidents

by energy of whatever serious or trifling cause

the shirt stays dirty

from that puppy’s paws

I take that fine white shirt

from India

the threads as soft as baby

fingers weaving them

together

and I wash that shirt

between

between the knuckles of my own

two hands

I scrub and rub that shirt

to take the dirty

markings

out

At the pocket

and around the shoulder seam

and on both sleeves

the dirt the paw

prints tantalize my soap

my water my sweat

equity

invested in the restoration

of a clean white shirt

And on the eleventh try

I see no more

no anything unfortunate

no dirt

I hold the limp fine

cloth

between the faucet stream

of water as transparent

as a wish the moon stayed out

all day

How small it has become!

That clean white shirt!

How delicate!

How slight!

How like a soft fist knocking on my door!

And now I hang the shirt

to dry

as slowly as it needs

the air

to work its way

with everything

It’s clean.

A clean white shirt

nobody wanted to spoil

or soil

that shirt

much cleaner now but also

not the same

as the first before that shirt

got hit got hurt

not perfect

anymore

just beautiful

a clean white shirt

It’s hard to keep a clean shirt clean.

*Sources: Poetry Foundation, Academy of American Poets, and back covers of the poets’ poetry collections are referred in the introductions above. Photos are from internet.

Calling all young poets, artists, and entrepreneurs! Showcase your creativity and sell your work at one of NYC’s most exciting cultural events—the New York City Poetry Festival on Governors Island! This is your chance to connect with fellow artists, poetry lovers, and a vibrant community ready to support young creators like you.

🌟 What You Get:

✅ Sell & Share Your Work – Whether it’s poetry chapbooks, art, handmade goods, or creative services, you have full permission to sell and promote your creations at the festival.

✅ Your Own Vendor Space – A shared table setup in our Youth Vendor Village! Each vendor gets dedicated space at a 6-foot table and two chairs.

✅ Be Part of the Festival Energy – Immerse yourself in a weekend of poetry, performance, and connection with a creative community that values youth voices.

💡 Important Details:

For Ages 18 & Under – This special rate is designed to support young creators looking to share their work with the world.

Non-Refundable – All vendor package purchases are final, so plan ahead!

Limited Spots Available – Secure yours early to guarantee your space!

🎤 Why Join?

✨ Visibility & Connection – Get your work in front of an engaged audience who appreciates creative expression.

✨ Supportive Community – Be part of an event that fosters youth creativity and artistic growth.

✨ Affordable & Accessible – At just $20, this is an amazing opportunity to gain real-world vendor experience without a big investment.

🚀 Reserve Your Spot Today! Spaces are limited, so sign up now and be part of NYC’s thriving poetry scene!