HOW TO POET

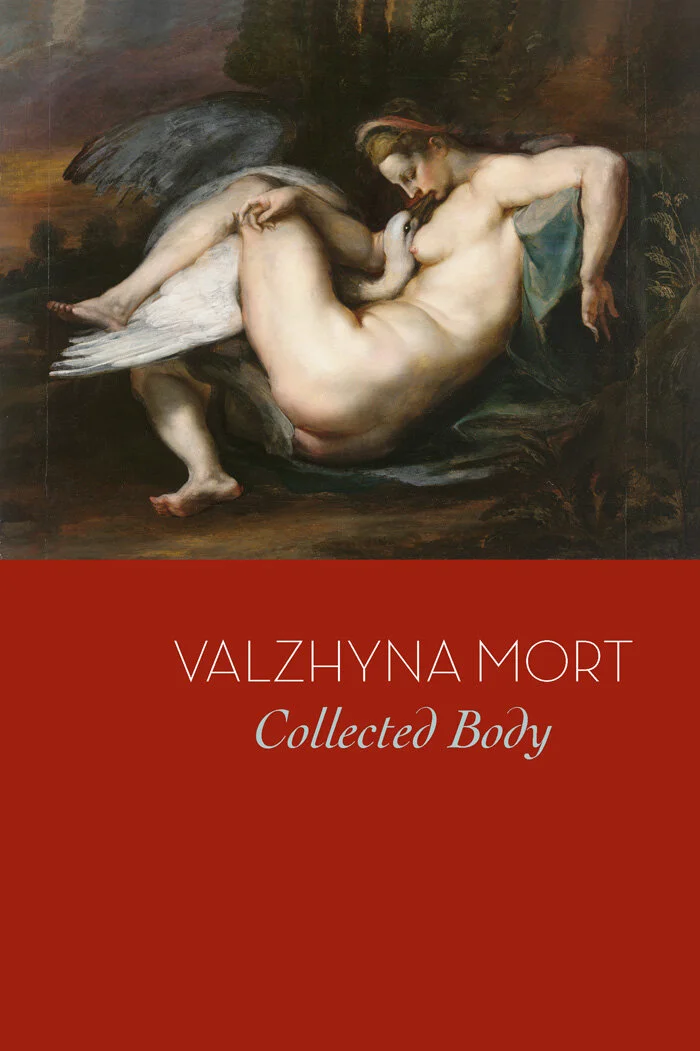

Clickbait Review: Valzhyna Mort's Collected Body

Belarusian poet Valzhyna Mort’s first collection written in English, Collected Body, is a complex tapestry of characters and their familial stories. In the collection, readers are constantly threatened by a sense of imminent death. Yet, instead of an end, death here becomes a means of union.

We at PSNY promise to publish only the most sincere book reviews and to only recommend products that we love. In the spirit of Clickbait, however, we want you to know that we will likely receive a portion of sales from products purchased through this article. Each click helps to support PSNY and Clickbait's writers directly, so we hope that you will use the links herein. Thank you for your support, dear readers!

Written by Yunqin Wang

Belarusian poet Valzhyna Mort’s first collection written in English, Collected Body, is a complex tapestry of characters and their familial stories. In the collection, readers are constantly threatened by a sense of imminent death. Yet, instead of an end, death here becomes a means of union.

Mort has placed her characters in their most vulnerable state, and at the same time let them fight off death in an extremely corporeal way. In Aunt Anna, the first prose poem of the book, Anna entered a childhood garden and “all she wanted to do was to eat” (28). In this way, “her belly couldn’t stop growing” (28). We are thus immediately introduced to the overarching metaphor between body and space, body and history in the collection. As Mort noted earlier in Aunt Anna that “A child...would learn that history had to be tangible like meat at dinner, but like meat at dinner, it also remained an abstraction” (19), we find the characters, in order to survive and to preserve their remaining relatives, try to fill up their physical bodies. It becomes their way to keep in contact with reality as well as history. In Zhenya, the second prose poem, the handicapped girl Zhenya moves from one place to another, yet gets lost. However, although lost in the physical world, she wishes for her body to extend — she “approaches that world…; reaches out for it… - insistently, aggressively, she knocks on the air, demands the air top open itself into something to walk through, to sit on, to lean against” (45). In the end, the swelling belly of Aunt Anna “became [her] younger brother”(28), and in the case of Zhenya, a classmate of the speaker, “we are finally pushed to reflect Zhenya in our own distorted ways.” (49)

The theme of reflection is not uncommon in the collection. To reconstruct each character’s personal history, Mort emphasizes how the characters are in relation with their intimate others. In Aunt Anna, for instance, thinking of her grandmother, the speaker feels “she bit [the teeth] through you, threaded a needle through the bites, and sewed you to that soil like a button….She threw over your head - a noose” (21). To assert her own existence, the speaker in Zhenya declares that her lover is “[her] plan for immortality”, “audience for [her] privacy” (49). In Island, “a road comes up to my face and stands like a mirror” (59). And at the end of Aunt Anna, Mort draws a surreal image which resembles the relationship of men to the world and to the dead, “... the building bared their hollowed heads and drained themselves into the eye sockets of the sleeping dead on the ground floors.” (25)

While death and memory are two main threads of the book, what makes Collected Body distinctive is how Mort tackles fearlessly taboo subjects, draws on raw physicality. Sylt I recounts an incest between an old father and four young sisters. However, the poem adopts neither an angry nor a harrowing tone. It is told calmly in an idyllic setting. The simile between body and food comes back. As the incest happens, “her teeth, crossed out by a blue line of lips, chatter, / scratching the grains of salt. Her bitter tongue / bleeds out into the mouth as red oyster, which she gulps, breathless.” The next stanza comes right in with the aftermath of the act, “Their father turns away to dry his cock” (7). Here, the violence, as a history desired to be erased, is expressed by the sister’s inability to digest. In contrast with Anna and Zhenya’s effort to enlarge their bodies, the girl feels “rough and indifferent toward her full breasts”. “It bothers her, what did he find there after all?” (7) Her body has become a shield crumbled, a vessel empty and evasive. Furthermore, the emotional distress of the speaker is expressed not through the description of her tormented flesh but the setting. “Sailboats slip off their white sarafans, / baring their scrawny necks and shoulders, / and line up holding on to the pier as if it were a dance bar.” (7) By stripping the subject of its horror, Mort has enabled us to look at the body and the story more clearly.

Just like her characters who resist to be erased from history, Mort also refuses to leave anyone out of her lyrics. The speaker whispers In Zhenya that “looking for Zhenya I find you” (49). In Aunt Anna, it is unavoidable to talk about Anna’s sister-in-law, young brother, husband, mother and children while the poem should be just about Anna. A new character is even introduced by the end of the poem. Mort writes, “A poem named after Aunt Anna, pages about Aunt Anna, and not one word about Boleska… (Boleska, if you are reading this, please find me, everybody is dead)” (32). The poet’s final attempt to refrain from the digression has failed, yet the introduction of Boleska is inescapable. It is both the result of the speaker’s wish to cling to her memories, and also because death ultimately united all.

Inevitably, all bodies decay in the end, yet Mort has seeked a way. In Love, located in a haunting apartment where “the neighbor is counting precious stones: / amiodarone, zofenopril, metoprolol, mexifin”, the speaker meditates, “Oh yes, she will inherit those jewels” (12). The jewel seems to be a hallmark that symbolizes the speaker’s awareness and acceptance of human mortality. By the end of the poem, the sweat of her lover “disperses, and multiples / like cockroaches” (13). Yet, remember the earlier stanza in the poem, “The spit shooting down the sink — / she still counts as his body. / The noose of his saliva over her pussy — / she still counts as his body… He folds her inside / and he ships her, and ships her, and ships…” (12) Mort, as well as all her characters, have given their stance before the unabashed acknowledgement of death: in this life journey, we should not leave anything, anyone out. And it’s with our bodies that we try to take in as much as we can.

Clickbait Review: Nathan Jurgenson's The Social Photo: On Photography and Social Media

By now it is no novel question to ask what the humanities owe the sciences, or indeed the sciences the humanities. The specture of the automaton is as old as the golem, which is to say as ancient as monotheism: this social anxiety regarding the essence of our humanity and its relationship to technology predates our modern conceptions of science. However, the meteoric rise in the social, political, and economic influence of technology companies such as Google, Apple, and Facebook demands that we continue reforming not only our answers to this question but our material responses to it. Social media theorist, editor emeritus of The New Inquiry, and sociologist at Snap Inc., Nathan Jurgenson addresses these disciplines via cyborg hybridity in his book The Social Photo: On Photography and Social Media.

We at PSNY promise to publish only the most sincere book reviews and to only recommend products that we love. In the spirit of Clickbait, however, we want you to know that we will likely receive a portion of sales from products purchased through this article. Each click helps to support PSNY and Clickbait's writers directly, so we hope that you will use the links herein. Thank you for your support, dear readers!

By now it is no novel question to ask what the humanities owe the sciences, or indeed the sciences the humanities. The specture of the automaton is as old as the golem, which is to say as ancient as monotheism: this social anxiety regarding the essence of our humanity and its relationship to technology predates our modern conceptions of science. However, the meteoric rise in the social, political, and economic influence of technology companies such as Google, Apple, and Facebook demands that we continue reforming not only our answers to this question but our material responses to it. Social media theorist, editor emeritus of The New Inquiry, and sociologist at Snap Inc., Nathan Jurgenson addresses these disciplines via cyborg hybridity in his book The Social Photo: On Photography and Social Media.

Written in 2.2 parts, The Social Photo is a brief but powerful exploration of the short history of photography, the even shorter history of social media, and the beginnings of their combination. The principle Jurgenson primarily returns to is historian Melvin Kranzberg's First Law of technology, which states: “Technology is neither good nor bad; nor is it neutral,” a refrain oft repeated by Jurgenson’s mentor Zeynep Tufekci in her influential Twitter and Tear Gas: The Power and Fragility of Networked Protest. Indeed, Jurgenson’s book marks the latest installment in a growing body of texts that urge us to, instead of rejecting technological advances, seek to take popular control of how they function.

Jurgenson rejects the “digital dualist dream behind so-called ‘cyber’ space and ‘virtual’ worlds,” arguing that our ‘true’ lives are not separate from the digital but infused with it. Our newfound obsession with “unplugging” to experience the somehow truer world “offline” stinks of digital influence: the heightened awareness of our lack of digital devices (and our obsession with then using those digital devices to announce our having been offline and what a Meaningful Experience™ it was via Twitter, magazine article, blog post, etc.) could only arise in the digital age, an age where the internet has extended beyond our devices and into our psychology. Just as photographers get “shutter eye” even when they are not carrying cameras, those of us who live in a world with social media begin seeing the world as Instagram-able, blog-able, record-able. Perhaps this renders the world consume-able in a way that seems unappealing, but is this so different from telling a story about our travels? Perhaps everything is (photo)copy after all.

The Social Photo is rife with references to the tensions inherent in photography between the ephemeral and the permanent, the copy and the original, the imitation and the authentic, the image and the world, what’s recorded and what’s outside the frame, indeed between the living with the dead. To take a photograph is to mediate upon mortality. The same has been said of writing poetry.

Over the course of photographic technology, the amount of time required to take, preserve, distribute a photograph has been decreasing to the point where it is now approaching zero, leading to dual impulses towards heightened permanence and heightened ephemerality. The craze circa 2010 of making digital photographs look like polaroids demonstrates this nostalgia for permanence and the hope that one’s digital photo might be imbued with the significance of an art object. This kind of social photo is demonstrated by more static interfaces such as the Instagram grid or a Facebook page. The impulse towards ephemerality works in the opposite way. Jurgenson develops an almost linguistic analysis of social photo use, stating that some social social photos such as jokes you might text to a friend, Snapchats, Instagram stories are designed to be snapped, viewed, and discarded, much like spoken language. This theory echoes linguist Gretchen McCulloch’s analysis of emoji and emoticon use as gesture in her book Because Internet. Images, particularly images of people, re-embody our discourse in the digital era. In the nineteenth century, reading novels was seen as scandalous: private, unhealthy, a distraction from conversation and more rigorous outdoor activities. Perhaps we should be no more concerned about our rapid escalation of image sharing than we now are about the proliferation of paperbacks.

Whatever our impulse in creating social photos--to record, to connect, to make art, to communicate--Jurgenson’s driving point in The Social Photo is that we live in a society and a social psychology which is now influenced by this kind of photography. Surely we, as a populace, would prefer to control the modes of production of the social photo than leave it up to large technology companies that profit off both our attention and our images? To some extent it seems like Jurgenson is putting his money where his mouth is--as a sociologist at Snap Inc. he surely seeks to influence the company in a leftist-populist direction--but any reader of Animal Farm knows, and I’d guess Jurgenson would agree, we should be suspicious of all who live in the farmer’s house and continue as a public to seek a truly democratic social landscape, both through the social photograph and otherwise.

Find more information about Jurgenson and his work here.

Written by Anna Winham

Clickbait Review: Kathleen McClung’s A Juror Must Fold in on Herself

The chapbook meditates on voice, how difficult it is to restrain our voices, how many of our voices are restrained by society.

We at PSNY promise to publish only the most sincere book reviews and to only recommend products that we love. In the spirit of Clickbait, however, we want you to know that we will likely receive a portion of sales from products purchased through this article. Each click helps to support PSNY and Clickbait's writers directly, so we hope that you will use the links herein. Thank you for your support, dear readers!

Kathleen McClung’s chapbook A Juror Must Fold in on Herself couldn’t have arrived at a better time for this sequestered reader, a juror in her own right. Several months into quarantine, interfacing with an unjust country from semi-permeable safety of my own solitude, I was turning in on myself, much like the sequestered juror of McClung’s bounded universe writing form poem after form poem. McClung writes in “Superior Court Ghazal,” “okay, so I may be over-/thinking here, but that’s what goes on in our little box.” At this point in time, who isn’t overthinking from her little box?

Some infinities are larger than others, but from where I’m sitting this still means that our small universes are infinite. If free verse is a large infinity, form poems are smaller ones. A villanelle, with its two repeating lines and strict rhyme scheme, seems restrictive, but the eternal lies here too. As poets know, no repetition is the identical. We cannot say the same thing twice. There is freedom to be found in restraint, and if we fold enough times we will soon be ten miles high.

This brief collection, restrained as it were, shifts voice poem by poem, from the District Attorney to the Public Defender to the Forewoman. Mostly we stick with the perspective of the Sequestered Juror, though, who figures in many forms: a rondeau, a pantoum, a sestina, a cento, a lament. She attempts time and again to order the tragedy at the centre of the book--what justice might be done about the death of a child--as though by organizing she might make sense of the senseless. We catch mere glimpses of the juror’s personhood; only small pieces of her life unfold: her mild attention to the “lanky prosecutor who doesn’t wear a ring,” her affection for her dog Alegria, her literary inclinations. We learn practically nothing of the defendant.

The chapbook meditates on voice, how difficult it is to restrain our voices, how many of our voices are restrained by society. From the very first poem, “Field Notes, Hall of Justice Parking Lot,” the juror longs to talk with the defendant but must not, for fear of being held in contempt of court. The Public Defender claims of the defendant, “his silence is his right” and later, “his silence is his choice,” though it does not seem like a choice. Meanwhile the Public Defender claims, “but me, I talk a lot,” and it’s unclear whether or not he is pleased with his own speech. An entire poem is composed of notes the juror does not write down; the poem is negative space, an absence, what could have been but was not, was held back. In the cento, she writes, “There are no words in our language to say this,” and yet what follows must certainly be the “this” she is saying. In the lament, speaking is one activity among a list of actions the jurors must not make. In the end, the juror prints her verdict on paper, and ultimately only the Forewoman speaks. At every point there is tension between silence and speech; a poem is never entirely one nor the other. A Juror Must Fold in on Herself builds the infinite into each small box.

All these meditations on silence, all these linguistic explorations of restraining the voice, all these foldings in on herself, open up into a sonnet crown ominously titled “Summons,” where the narrator seeks advice from her late grandmother, a courthouse stenographer, on how to conduct her legally imposed silence. Here it is the narrator who speaks, despite her enforced silence, while the grandmother, called on for advice, remains silent. Here we truly meet the narrator for the first time, see the fuller fabric of her life intertwined through her grandmother’s, and we see in parallel the humanization of the legal proceedings. The play of the title, the narrator invoking the presence of her dead ancestor and the court requiring one’s presence, emphasizes this entwining.

Though the grandmother does not give advice, the collection ultimately does, ending on two sonnets titled, “Advice for the Ghost Ship Jurors,” addressing the fire that broke out in an artists’ collective in Oakland in 2016 and killed 36 people. These final poems emphasize the jurors’ humanity in the face of mass, senseless tragedy. As readers trapped in my own small boxes, perhaps enduring forced silences of our own, these final poems serve as reminders that we are jurors of mass, mass tragedy. They urge us to expand. While this collection may resonate particularly well in our time of quarantine and a renewed social awareness of injustice, irreconcilable tragedies are a permanent feature of our lives, and McClung’s treatise with these poems is that we must not lose our humanity when we respond to them, and we must never descend into silence.

Learn more about McClung and her work here.

Written by Anna Winham