HOW TO POET

Book Review: The Beautiful Immunity by Karen An-Hwei Lee

Read Emi Bergquist’s book review on The Beautiful Immunity by Karen An-Hwei Lee and explore what it means to be immune—not just in the biological sense, but in the spiritual, emotional, and linguistic realms.

A Beautiful Immunity: On Language, Healing, and the Mysticism of Survival in Karen An-Hwei Lee’s Latest Collection

What does it mean to be immune—not just in the biological sense, but in the spiritual, emotional, and linguistic realms? In The Beautiful Immunity, Karen An-Hwei Lee crafts a poetic lexicon of survival, one that moves fluidly between the scientific and the surreal, between prayer and a deep, almost alchemical reverence for language. This collection pulses with lyricism, its precision sharpened by a careful unraveling of sound, breath, and absence. Yet, even in its most meditative silences, Lee’s work resists retreat. Instead, these poems seek an expansive form of protection—through words, through faith, through the body’s ability to adapt.

From the title alone, The Beautiful Immunity suggests a duality: a shield that is also an aesthetic, a survival that does not merely endure but transforms. Immunity, in Lee’s hands, is more than a bodily defense—it is a poetics of resilience, a response to both environmental and spiritual precarity.

In “Dear Millennium, on the Beautiful Immunity”, Lee’s speaker addresses the 21st century with a mixture of irony and supplication, asking for reprieve from a world marked by contamination, both biological and ideological. The poem opens with a tone that is both wistful and defiant:

“Dear millennium, you never promised to give me

a full strawberry moon, or amnesty from bioexile,

or genetically modified honey and roasted stone fruit.

Will the moon fall out of the sky?”

Here, there is a subtle critique of modernity’s broken promises. The millennium, personified, is both an era and an indifferent force, a time of technological and medical advancement but also of exile and estrangement. The phrase “bioexile” suggests a sense of displacement at the level of the body, a world where genetic modification has seeped into even the most fundamental aspects of sustenance—honey, fruit, immunity itself.

As the poem progresses, Lee tightens the critique, pivoting to environmental degradation and xenophobia:

“Please don’t feel obliged to love me back. Instead, grant me a beautiful immunity

to viral strains with evolved vaccine resistance—

zika of fetal microencephaly, chronic fatigue syndrome,

plagues of dyspepsia and dysthymia in the nervous weather of vulnerability—”

The juxtaposition of scientific terminology with poetic phrasing, “the nervous weather of vulnerability”, underscores Lee’s ability to fuse the clinical and the lyrical. This is a world where illness and emotional fragility blur into each other, where even the body’s natural defenses are compromised by forces beyond its control. The closing lines drive home the final act of defiance:

Don’t worry about loving me until death do us part—

I’m immune to your pathologies, my dear.”

By reframing immunity as both a biological and emotional resistance, Lee challenges the reader to consider what forms of protection are truly possible in an era of pandemics, environmental collapse, and cultural alienation.

One of the most striking elements of The Beautiful Immunity is Lee’s ability to oscillate between precise, almost clinical language and moments of dreamlike surrealism. Nowhere is this contrast more apparent than in “Seven Cantos on Silence as Via Negativa”, where Lee unspools silence into a series of shifting metaphors:

“Neither is the word silence equivalent to the loveliest of lovely days

beginning with love and lengthening with the light

where an open parenthesis never closes—”

Silence, rather than being an absence, is given form here—it stretches and lengthens, its presence signified by an “open parenthesis” that never resolves. The interplay between syntax and meaning is crucial; the hanging dash at the end of the line visually enacts the unresolved nature of silence, its ongoing, unbroken presence.

Later, in Canto 2, Lee extends the metaphor into something more fragile, almost architectural:

“Neither is it an invisible flock of small n-dashes

flying in hyphens of horizontal light to a skyline

where little nothings brush the air with em-dashes

as pauses or broken spaces—”

Here, punctuation itself becomes a stand-in for sound and breath. The precise choice of “n-dashes” and “em-dashes” transforms typographic elements into something kinetic, birdlike. This is silence in motion, a landscape of absence constructed through the delicate balance of pause and space.

Yet, even as Lee leans into meticulous control, she is unafraid to let her language unravel into something more hallucinatory. In “On Levitation at the Carp-Tail Sugar Factory”, she crafts an image of defiance against gravity, where small objects and bodies alike resist the expected laws of physics:

“As if the levitation of miniature objects is a surprise—

scale isn’t a miracle of perception

or fruit of anti-gravity.

A robin’s egg on the palm of my hand, aloft in June—

bird-soul’s turquoise belt.”

The phrase “scale isn’t a miracle of perception” suggests a rejection of illusion—levitation, in this context, is not merely a trick of the eyes but something inherent to the objects themselves. This speaks to a broader thematic concern in Lee’s work: the idea that survival, resilience, and even beauty are not illusions, but deeply rooted in the fabric of existence.

Throughout The Beautiful Immunity, spirituality is not just a theme but a mode of inquiry. Lee’s work is deeply engaged with mysticism, not as dogma but as a poetic method for understanding the world. In “Irenology”, she explicitly ties poetry to the act of peace-making, invoking biblical imagery alongside notions of exile and restoration:

“Open in Ezra and paging to Nehemiah,

I contemplate exiles rebuilding temple walls.

I thought, is this a form of peace studies?”

Here, the act of rebuilding—both literal and metaphorical—becomes a spiritual practice. The poem moves between religious devotion and historical reckoning, asking how peace circulates and whether it can be reconstructed, much like the temple walls.

This preoccupation with spiritual paradox reaches its most haunting expression in “Zona Negativa”, a poem that loops on itself, echoing phrases like a chant or incantation:

“solo

alight and over—

humming our souls

arisen, a redolence of God,

fragrance, a myrrh residue,

offering splendid zones of salvage—”

The repetition of “solo” at both the beginning and end creates a circular, meditative effect, reinforcing the solitude of the speaker’s spiritual searching. The phrase “splendid zones of salvage” is particularly arresting—it suggests that even within destruction, there are places where something sacred can be recovered.

Karen An-Hwei Lee’s The Beautiful Immunity is a book of paradoxes: silence that is full, immunity that is fragile, survival that is both scientific and mystical. Through lyrical precision and surreal flourish, she crafts a poetic space where language itself becomes a form of resilience—a way to navigate illness, uncertainty, and a world in flux. In the end, these poems do not promise invulnerability. Rather, they suggest that true immunity is not about avoidance, but about adaptation, about finding a voice that resists even as it sings.

Emi Bergquist (she/her) is a New York based poet, performer, and content creator. An active member of The Poetry Society of New York since 2015, her has work published in over ten literary journals including The Headlight Review, What Rough Beast, Oxford Public Philosophy, Oroboro, Passengers Journal, For Women Who Roar, Noctua Review, In Parentheses, and others. When not reading or writing poetry, Emi prefers to spend most of her time at the park with her rescue dog, Zola.

The Ideal Object for You, Based on Your Zodiac Sign

We’ve narrowed down the perfect Ideal Object for you, based on your zodiac sign (otherwise known as your sun sign).

If you’ve looked through our online store recently, you’ve probably noticed that there’s a lot to choose from. No fear! We have a solution. We’ve narrowed down the perfect Ideal Object for you, based on your zodiac sign (otherwise known as your sun sign). Below apply your DOB and we’ll help you find exactly what you’re looking for.

What’s an Ideal Object? We’re glad you asked. Ideal Objects is a series of product collaborations between PSNY’s design team and a poet, artist, or collective who sought to manifest their vision of that product’s formal ideal. Ideal Objects was created during the COVID-19 pandemic in order to create opportunities for remote collaboration and to help generate income for artists who lost work. Each of the items in our Ideal Objects line is a collaboration, & 20% of each sale goes directly to the collaborating artists. If you’re interested in submitting a design follow this link: Ideal Objects - Submission Form

Aquarius

(Jan 20 - Feb 18)

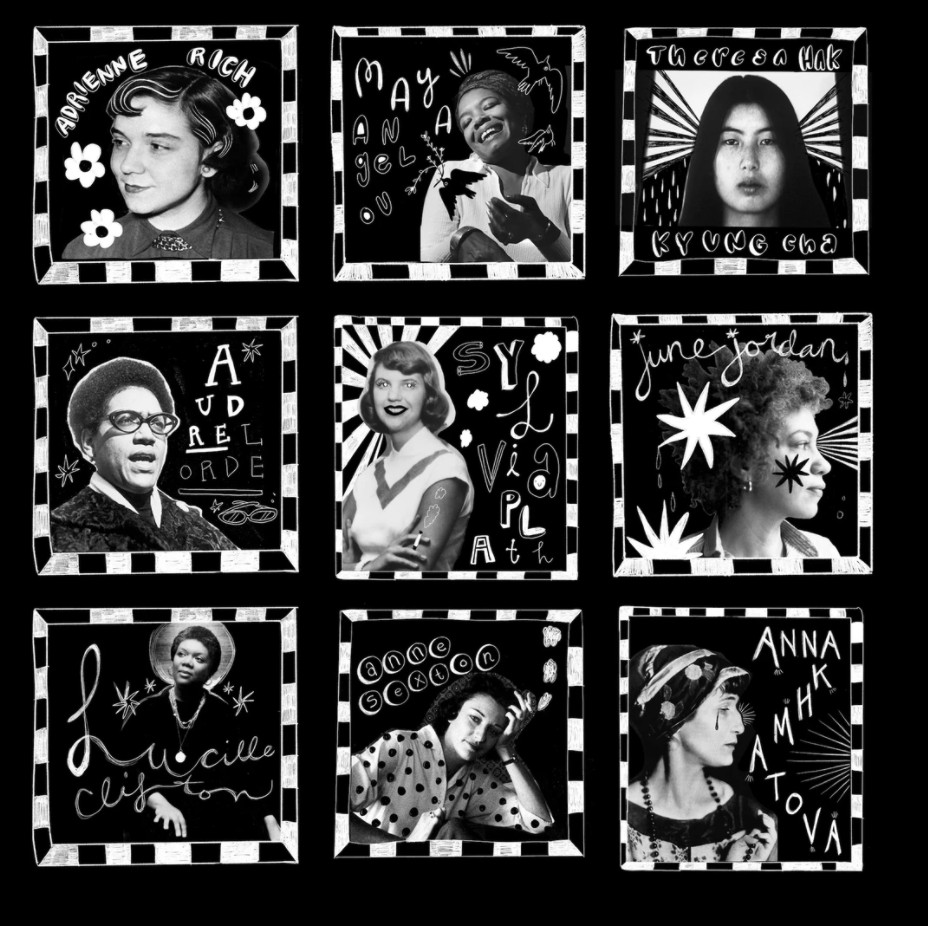

The intellectual and visionary thinkers of the zodiac. No other sign uses their mind quite like you do to achieve their goals. Not only is your intellectual prowess able to expand the world into a realm of possibilities, but you utilize your surroundings in a way that takes your ideas to the next level. In simpler terms, you are independent, progressive, and energetic, despite a world that pressures constant conformity. Those who dawn an Aquarian sun sign are recognized for breaking away from the mold and aspiring towards radical change. We encourage you to join forces with fellow Aquarian poet Audre Lorde, a self-described “black, lesbian, mother, warrior, poet.” Known for harnessing her creative talent to confront social injustice, Audre Lorde embodies what it means to be a transformative Aquarius. Throughout her life, she stuck to her intuitions to harness positive action and change within her community. Who’s to say that can’t also be you? Keep Lorde by your side Aquarians, and you’ll be capable of manifesting your visions towards a better tomorrow and carry us into the next millennium.

Pisces

(Feb 19 - March 20)

The selfless and compassionate Pisces. You use your creativity to express your emotional capacity and to help others. You have an innate understanding of your emotional relationships and how to care for others in ways that are never judgmental or overbearing. With your connection to others, communication is important to you to resolve problems and create a sense of overruling unity. But how do you invoke communication out of the avoidant personalities around us? One skillset that you have mastered is creating organic spaces where honest discussions can arise with your partners to create emotionally fulfilling bonds. We want to help you with that… during the next few months grab we encourage you to spend time with your family and relax on the couch with the “Heart like a Fist” pillow or even use it to take a nap and give your tender heart a break.

Aries

(March 21 - April 19)

Aries, you are headstrong, determined, and are always ready to meet a challenge no matter the obstacle. Your energy is infinite, bold, ambitious, which allows you to work on multiple projects keeping you one step ahead of the crowd. It’s no wonder your sign is associated with the ram you are consistently leaning towards progress. Your futuristic perspective knows no bounds. On any given day, you’re working towards your goals and trying to get the most of what’s laid out in front of you. We’re recommending you the Maya Angelou Lady Poet T-Shirt as your identifying Ideal Object pick. Talk about garnering success, Angelou was awarded over 50 honorary degrees before her passing in 2014. Not only is she a famous Aries but she is known for garnering immense respect through her craft and never let others sway her on her intuitions. Aries, keep her in mind when working on your upcoming projects to access your unique ability to problem solve

Taurus

(April 20 - March 20)

One of the more well-grounded signs, Taurus, you are an Earth sign that provides realistic perspectives and stays with projects until they complete. You have a passion for creating beauty in the spaces you’re in and are capable of putting in the work to achieve it. As one of the hardest-working signs, you look to build strong and reliable partnerships out of honesty and passion. We want you to bring everything you need around with you in a way that represents who you are. Carry all your poems and projects into 2021 with our Survival of the Beautiful Tote. Not only is this tote a functional and dependable piece, but it’s artistic and environmentally friendly too. We know you’ll have a long-term relationship with this bag as you’ll use it to bring your vision into the world around you. Plus, we know if there’s anyone who can survive 2020 and 2021 it’s a Taurus sun sign.

Gemini

(March 21 - June 20)

Geminis, you are expressive and curious making you inspiring artists and flexible with your skills. One of the more social creatures within the zodiac, you need variety and excitement in your life to stay interested. Luckily, we’ve never met a boring Gemini. You’re constantly drawn to the outside world and are extremely inquisitive. It’s one of the many things we love about you. When it comes to the Geminis it’s hard for us to pick an Ideal Object. That’s why we’re picking more than just one… well more than just one of the ladies that is. You get to enjoy the All the Lady Poets T-Shirt today and into 2021. Paired together these women make up a strong team of divine feminine power in many different ways. We can’t wait to see what you will do in 2021 as you work with all the people you meet and harness the lady poet’s diverse abilities.

Cancer

(June 21 - July 22)

Oh, there is so much to say about the tenacious, loyal, and imaginative Cancer. You deeply care about the people around you and are easily able to tap into their emotions with your intuition. This may not come out first, because like many other signs you try to keep your heart guarded. Yet, with a bit of time and patience, others see your gentle nature and authentic compassion. With all the ideal qualities for a poet, we really could pick any Ideal Object for you. However, as we’ve entered into 2021 and a new season of creativity, we’re calling on the energy of June Jordan, a famous fellow Cancer to represent you. Jordan used her creative talent to not only express her feelings about the world around her but her own emotional desires and wounds. Much of her works were autobiographical but still had the special ability to reach a broad audience. This year we hope that you’ll continue cultivating your emotional depth like Jordan to create tender masterpieces.

Leo

(July 23 - August 22)

The spotlight is on Leo *wink wink*. We know that you’re a star, you know you’re a star, gosh, the red carpet is rolled out and ready for you. Even thinking of your name, Leo, brings us back to the king of the jungle and the commanding presence you demand upon entering a room. You’re well aware of the importance of celebrating one’s personal victories and achievements. That’s not to say that you’re not also capable of stable and meaningful relationships, after all, everyone needs fans. In fact, many know that the mark of true Leo sun signs is the abundant loyalty and consistency they provide to their friends, family, and lovers. So, what Ideal Object can embody all a Leo has to offer? We think we know just the right one. Bold, bright, and dependable you remind us of our Poems! Tote. You are a bold statement when entering a room that people can’t ignore. Why not make that statement literary?

Virgo

(August 23 - September 22)

The lovely Virgo maiden floats through life effortlessly, yet is practical, strategic, and logical. A sun sign that exudes a sort of perfectionism that is hard to ignore, Virgo, you offer creative expression with keen eyes and motivated hands. This meticulousness in everyday life can be intimidating to those around you. But those who know you know your natural empathy and tenderness. Your resourcefulness and ability to organize directly impact your relationships. This makes you a kind and reliable friend to those who invest in your life. Whether it’s coffee to get ideas flowing, a way to store your stationery, or a fun gift for a friend the PSNY Watercolor Mug is useful to any and all Virgos. Let’s be honest, who doesn’t love a mug? Between the hardworking hours of the day that you and your loved ones put in, it’s important to have a grounding point in a coffee break, teatime, or even just to hydrate. We won’t keep you too long, we know you have important plans, and we can’t wait to see them.

Libra

(September 23 - October 22)

We’ve been expecting you Libras. Knowing your eye for the arts and your intellectualism, you gravitate towards the finer things in life. At the same time, you are a sun sign in the zodiac that resembles balance and harmony making you great companions and partners. We’ve never met anyone who doesn’t love a Libra. Have you? That’s why we wanted to pick an Ideal Object that caught the eye and kept you there. Add a splash of pink and poetry into your life with the Raspberry Sorbet Summer Pillow. Unique in the Perfect Circle Pillows line, this PSNY pillow doesn’t ask for favors but is perfect and comfortable as it is. Much like a Libra, it exudes brightness, charm, and compatibility in the spaces it inhabits. As you maintain your relationships with your friends and lovers, take a seat and take in everything that you’ve been able to create for yourself. We’ll be right beside you with a few verses just for you.

Scorpio

(October 23 - November 21)

You are seductive, mysterious, and full of depth. Scorpio, no one will quite understand you as much as you know yourself. Within the zodiac, you are known for your ambition and intensity, but it can often be a turn-off to other signs who assume that you are egotistical and stubborn. They forget that while you are secretive, you also are a part of the water family and are deeply entrenched in your emotions. Let’s not forget that some people are just better at concealing their emotions than others. Yet, the connection that you do form lasts a lifetime and is full of intimacy and unwavering trust. Who else could we give you to represent within our Ideal Object series than Sylvia Plath, another famous Scorpio sun sign? Plath is known for having poetry with darker elements and deep emotions that for some can render unease and in others understanding. It’s a tight line to walk, but someone has to do it, and we know that Scorpios are always up for a challenge.

Sagittarius

(November 22 - Dec 21)

What’s next? Something we’re always asking ourselves when it comes to Sagittarius. You see life as an adventure and a chance to expand your mind. Quick, witty, and likable you go into different spaces with ease knowing that you can win others over with your charm and social skills. At the same time, we don’t expect to hold onto you for so long because you are constantly in motion to find different avenues of change. With all of the places you expect to end up going, you’re going to need something to carry all your possessions but in true Sag form. Since you’re full of possibilities, we think the Love in Time of Covid Tote works perfectly for all of your expeditions. As the saying implies, there is still room for abundance in our lives despite difficulties. If there’s a sign that embodies this in the zodiac it’s surely Sagittarius.

Capricorn

(Dec 22 - Jan 19)

A grounded earth sign, Capricorns, you are characterized with ambition, drive, and endurance. When it comes to your goals, you have an intensity that allows you to achieve them quickly and without distraction. On the same hand a marking sign of Capricorns maturing as they age. For many Capricorns, as you age and become older your personality becomes more carefree and your work-life balance levels out. When you do get some downtime between your goals and this emotional transition, we hope you’ll take advantage of the Coffee All the Time Pillow, which is a part of our Perfect Circle Pillow Collection. Or if you’re not willing to take a break quite yet, use it as a backrest in your office chair and a reminder to fill your cup.

That’s a wrap! We hope this helped find your Ideal Object! Find more of our store items and merch here: PSNY Shop

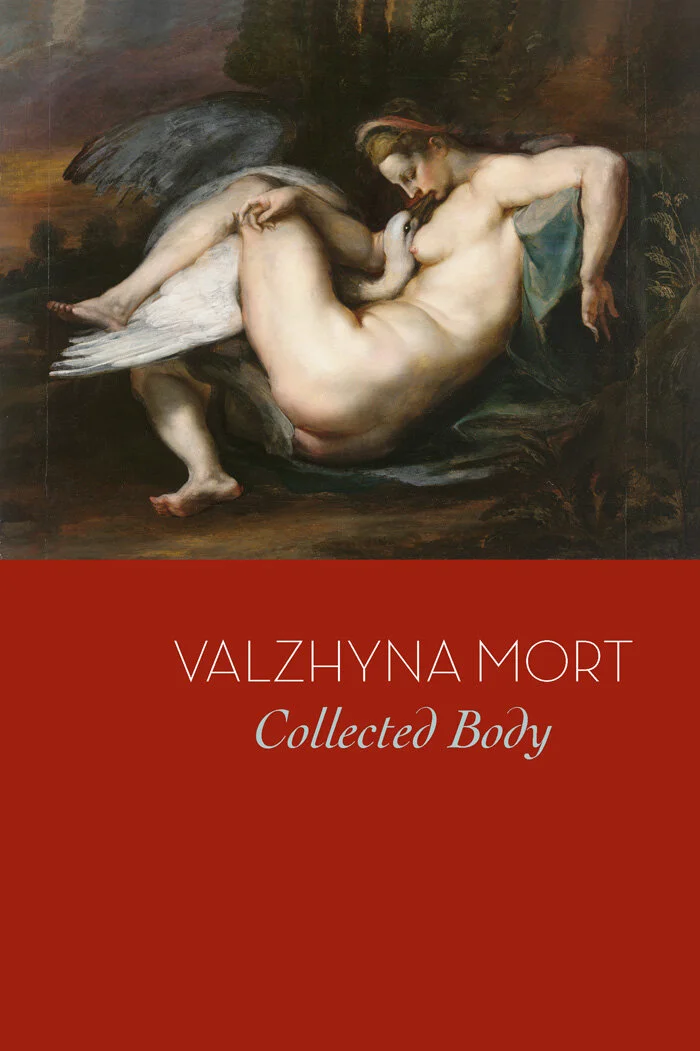

Clickbait Review: Valzhyna Mort's Collected Body

Belarusian poet Valzhyna Mort’s first collection written in English, Collected Body, is a complex tapestry of characters and their familial stories. In the collection, readers are constantly threatened by a sense of imminent death. Yet, instead of an end, death here becomes a means of union.

We at PSNY promise to publish only the most sincere book reviews and to only recommend products that we love. In the spirit of Clickbait, however, we want you to know that we will likely receive a portion of sales from products purchased through this article. Each click helps to support PSNY and Clickbait's writers directly, so we hope that you will use the links herein. Thank you for your support, dear readers!

Written by Yunqin Wang

Belarusian poet Valzhyna Mort’s first collection written in English, Collected Body, is a complex tapestry of characters and their familial stories. In the collection, readers are constantly threatened by a sense of imminent death. Yet, instead of an end, death here becomes a means of union.

Mort has placed her characters in their most vulnerable state, and at the same time let them fight off death in an extremely corporeal way. In Aunt Anna, the first prose poem of the book, Anna entered a childhood garden and “all she wanted to do was to eat” (28). In this way, “her belly couldn’t stop growing” (28). We are thus immediately introduced to the overarching metaphor between body and space, body and history in the collection. As Mort noted earlier in Aunt Anna that “A child...would learn that history had to be tangible like meat at dinner, but like meat at dinner, it also remained an abstraction” (19), we find the characters, in order to survive and to preserve their remaining relatives, try to fill up their physical bodies. It becomes their way to keep in contact with reality as well as history. In Zhenya, the second prose poem, the handicapped girl Zhenya moves from one place to another, yet gets lost. However, although lost in the physical world, she wishes for her body to extend — she “approaches that world…; reaches out for it… - insistently, aggressively, she knocks on the air, demands the air top open itself into something to walk through, to sit on, to lean against” (45). In the end, the swelling belly of Aunt Anna “became [her] younger brother”(28), and in the case of Zhenya, a classmate of the speaker, “we are finally pushed to reflect Zhenya in our own distorted ways.” (49)

The theme of reflection is not uncommon in the collection. To reconstruct each character’s personal history, Mort emphasizes how the characters are in relation with their intimate others. In Aunt Anna, for instance, thinking of her grandmother, the speaker feels “she bit [the teeth] through you, threaded a needle through the bites, and sewed you to that soil like a button….She threw over your head - a noose” (21). To assert her own existence, the speaker in Zhenya declares that her lover is “[her] plan for immortality”, “audience for [her] privacy” (49). In Island, “a road comes up to my face and stands like a mirror” (59). And at the end of Aunt Anna, Mort draws a surreal image which resembles the relationship of men to the world and to the dead, “... the building bared their hollowed heads and drained themselves into the eye sockets of the sleeping dead on the ground floors.” (25)

While death and memory are two main threads of the book, what makes Collected Body distinctive is how Mort tackles fearlessly taboo subjects, draws on raw physicality. Sylt I recounts an incest between an old father and four young sisters. However, the poem adopts neither an angry nor a harrowing tone. It is told calmly in an idyllic setting. The simile between body and food comes back. As the incest happens, “her teeth, crossed out by a blue line of lips, chatter, / scratching the grains of salt. Her bitter tongue / bleeds out into the mouth as red oyster, which she gulps, breathless.” The next stanza comes right in with the aftermath of the act, “Their father turns away to dry his cock” (7). Here, the violence, as a history desired to be erased, is expressed by the sister’s inability to digest. In contrast with Anna and Zhenya’s effort to enlarge their bodies, the girl feels “rough and indifferent toward her full breasts”. “It bothers her, what did he find there after all?” (7) Her body has become a shield crumbled, a vessel empty and evasive. Furthermore, the emotional distress of the speaker is expressed not through the description of her tormented flesh but the setting. “Sailboats slip off their white sarafans, / baring their scrawny necks and shoulders, / and line up holding on to the pier as if it were a dance bar.” (7) By stripping the subject of its horror, Mort has enabled us to look at the body and the story more clearly.

Just like her characters who resist to be erased from history, Mort also refuses to leave anyone out of her lyrics. The speaker whispers In Zhenya that “looking for Zhenya I find you” (49). In Aunt Anna, it is unavoidable to talk about Anna’s sister-in-law, young brother, husband, mother and children while the poem should be just about Anna. A new character is even introduced by the end of the poem. Mort writes, “A poem named after Aunt Anna, pages about Aunt Anna, and not one word about Boleska… (Boleska, if you are reading this, please find me, everybody is dead)” (32). The poet’s final attempt to refrain from the digression has failed, yet the introduction of Boleska is inescapable. It is both the result of the speaker’s wish to cling to her memories, and also because death ultimately united all.

Inevitably, all bodies decay in the end, yet Mort has seeked a way. In Love, located in a haunting apartment where “the neighbor is counting precious stones: / amiodarone, zofenopril, metoprolol, mexifin”, the speaker meditates, “Oh yes, she will inherit those jewels” (12). The jewel seems to be a hallmark that symbolizes the speaker’s awareness and acceptance of human mortality. By the end of the poem, the sweat of her lover “disperses, and multiples / like cockroaches” (13). Yet, remember the earlier stanza in the poem, “The spit shooting down the sink — / she still counts as his body. / The noose of his saliva over her pussy — / she still counts as his body… He folds her inside / and he ships her, and ships her, and ships…” (12) Mort, as well as all her characters, have given their stance before the unabashed acknowledgement of death: in this life journey, we should not leave anything, anyone out. And it’s with our bodies that we try to take in as much as we can.

Clickbait Review: Nathan Jurgenson's The Social Photo: On Photography and Social Media

By now it is no novel question to ask what the humanities owe the sciences, or indeed the sciences the humanities. The specture of the automaton is as old as the golem, which is to say as ancient as monotheism: this social anxiety regarding the essence of our humanity and its relationship to technology predates our modern conceptions of science. However, the meteoric rise in the social, political, and economic influence of technology companies such as Google, Apple, and Facebook demands that we continue reforming not only our answers to this question but our material responses to it. Social media theorist, editor emeritus of The New Inquiry, and sociologist at Snap Inc., Nathan Jurgenson addresses these disciplines via cyborg hybridity in his book The Social Photo: On Photography and Social Media.

We at PSNY promise to publish only the most sincere book reviews and to only recommend products that we love. In the spirit of Clickbait, however, we want you to know that we will likely receive a portion of sales from products purchased through this article. Each click helps to support PSNY and Clickbait's writers directly, so we hope that you will use the links herein. Thank you for your support, dear readers!

By now it is no novel question to ask what the humanities owe the sciences, or indeed the sciences the humanities. The specture of the automaton is as old as the golem, which is to say as ancient as monotheism: this social anxiety regarding the essence of our humanity and its relationship to technology predates our modern conceptions of science. However, the meteoric rise in the social, political, and economic influence of technology companies such as Google, Apple, and Facebook demands that we continue reforming not only our answers to this question but our material responses to it. Social media theorist, editor emeritus of The New Inquiry, and sociologist at Snap Inc., Nathan Jurgenson addresses these disciplines via cyborg hybridity in his book The Social Photo: On Photography and Social Media.

Written in 2.2 parts, The Social Photo is a brief but powerful exploration of the short history of photography, the even shorter history of social media, and the beginnings of their combination. The principle Jurgenson primarily returns to is historian Melvin Kranzberg's First Law of technology, which states: “Technology is neither good nor bad; nor is it neutral,” a refrain oft repeated by Jurgenson’s mentor Zeynep Tufekci in her influential Twitter and Tear Gas: The Power and Fragility of Networked Protest. Indeed, Jurgenson’s book marks the latest installment in a growing body of texts that urge us to, instead of rejecting technological advances, seek to take popular control of how they function.

Jurgenson rejects the “digital dualist dream behind so-called ‘cyber’ space and ‘virtual’ worlds,” arguing that our ‘true’ lives are not separate from the digital but infused with it. Our newfound obsession with “unplugging” to experience the somehow truer world “offline” stinks of digital influence: the heightened awareness of our lack of digital devices (and our obsession with then using those digital devices to announce our having been offline and what a Meaningful Experience™ it was via Twitter, magazine article, blog post, etc.) could only arise in the digital age, an age where the internet has extended beyond our devices and into our psychology. Just as photographers get “shutter eye” even when they are not carrying cameras, those of us who live in a world with social media begin seeing the world as Instagram-able, blog-able, record-able. Perhaps this renders the world consume-able in a way that seems unappealing, but is this so different from telling a story about our travels? Perhaps everything is (photo)copy after all.

The Social Photo is rife with references to the tensions inherent in photography between the ephemeral and the permanent, the copy and the original, the imitation and the authentic, the image and the world, what’s recorded and what’s outside the frame, indeed between the living with the dead. To take a photograph is to mediate upon mortality. The same has been said of writing poetry.

Over the course of photographic technology, the amount of time required to take, preserve, distribute a photograph has been decreasing to the point where it is now approaching zero, leading to dual impulses towards heightened permanence and heightened ephemerality. The craze circa 2010 of making digital photographs look like polaroids demonstrates this nostalgia for permanence and the hope that one’s digital photo might be imbued with the significance of an art object. This kind of social photo is demonstrated by more static interfaces such as the Instagram grid or a Facebook page. The impulse towards ephemerality works in the opposite way. Jurgenson develops an almost linguistic analysis of social photo use, stating that some social social photos such as jokes you might text to a friend, Snapchats, Instagram stories are designed to be snapped, viewed, and discarded, much like spoken language. This theory echoes linguist Gretchen McCulloch’s analysis of emoji and emoticon use as gesture in her book Because Internet. Images, particularly images of people, re-embody our discourse in the digital era. In the nineteenth century, reading novels was seen as scandalous: private, unhealthy, a distraction from conversation and more rigorous outdoor activities. Perhaps we should be no more concerned about our rapid escalation of image sharing than we now are about the proliferation of paperbacks.

Whatever our impulse in creating social photos--to record, to connect, to make art, to communicate--Jurgenson’s driving point in The Social Photo is that we live in a society and a social psychology which is now influenced by this kind of photography. Surely we, as a populace, would prefer to control the modes of production of the social photo than leave it up to large technology companies that profit off both our attention and our images? To some extent it seems like Jurgenson is putting his money where his mouth is--as a sociologist at Snap Inc. he surely seeks to influence the company in a leftist-populist direction--but any reader of Animal Farm knows, and I’d guess Jurgenson would agree, we should be suspicious of all who live in the farmer’s house and continue as a public to seek a truly democratic social landscape, both through the social photograph and otherwise.

Find more information about Jurgenson and his work here.

Written by Anna Winham

Clickbait Review: Kathleen McClung’s A Juror Must Fold in on Herself

The chapbook meditates on voice, how difficult it is to restrain our voices, how many of our voices are restrained by society.

We at PSNY promise to publish only the most sincere book reviews and to only recommend products that we love. In the spirit of Clickbait, however, we want you to know that we will likely receive a portion of sales from products purchased through this article. Each click helps to support PSNY and Clickbait's writers directly, so we hope that you will use the links herein. Thank you for your support, dear readers!

Kathleen McClung’s chapbook A Juror Must Fold in on Herself couldn’t have arrived at a better time for this sequestered reader, a juror in her own right. Several months into quarantine, interfacing with an unjust country from semi-permeable safety of my own solitude, I was turning in on myself, much like the sequestered juror of McClung’s bounded universe writing form poem after form poem. McClung writes in “Superior Court Ghazal,” “okay, so I may be over-/thinking here, but that’s what goes on in our little box.” At this point in time, who isn’t overthinking from her little box?

Some infinities are larger than others, but from where I’m sitting this still means that our small universes are infinite. If free verse is a large infinity, form poems are smaller ones. A villanelle, with its two repeating lines and strict rhyme scheme, seems restrictive, but the eternal lies here too. As poets know, no repetition is the identical. We cannot say the same thing twice. There is freedom to be found in restraint, and if we fold enough times we will soon be ten miles high.

This brief collection, restrained as it were, shifts voice poem by poem, from the District Attorney to the Public Defender to the Forewoman. Mostly we stick with the perspective of the Sequestered Juror, though, who figures in many forms: a rondeau, a pantoum, a sestina, a cento, a lament. She attempts time and again to order the tragedy at the centre of the book--what justice might be done about the death of a child--as though by organizing she might make sense of the senseless. We catch mere glimpses of the juror’s personhood; only small pieces of her life unfold: her mild attention to the “lanky prosecutor who doesn’t wear a ring,” her affection for her dog Alegria, her literary inclinations. We learn practically nothing of the defendant.

The chapbook meditates on voice, how difficult it is to restrain our voices, how many of our voices are restrained by society. From the very first poem, “Field Notes, Hall of Justice Parking Lot,” the juror longs to talk with the defendant but must not, for fear of being held in contempt of court. The Public Defender claims of the defendant, “his silence is his right” and later, “his silence is his choice,” though it does not seem like a choice. Meanwhile the Public Defender claims, “but me, I talk a lot,” and it’s unclear whether or not he is pleased with his own speech. An entire poem is composed of notes the juror does not write down; the poem is negative space, an absence, what could have been but was not, was held back. In the cento, she writes, “There are no words in our language to say this,” and yet what follows must certainly be the “this” she is saying. In the lament, speaking is one activity among a list of actions the jurors must not make. In the end, the juror prints her verdict on paper, and ultimately only the Forewoman speaks. At every point there is tension between silence and speech; a poem is never entirely one nor the other. A Juror Must Fold in on Herself builds the infinite into each small box.

All these meditations on silence, all these linguistic explorations of restraining the voice, all these foldings in on herself, open up into a sonnet crown ominously titled “Summons,” where the narrator seeks advice from her late grandmother, a courthouse stenographer, on how to conduct her legally imposed silence. Here it is the narrator who speaks, despite her enforced silence, while the grandmother, called on for advice, remains silent. Here we truly meet the narrator for the first time, see the fuller fabric of her life intertwined through her grandmother’s, and we see in parallel the humanization of the legal proceedings. The play of the title, the narrator invoking the presence of her dead ancestor and the court requiring one’s presence, emphasizes this entwining.

Though the grandmother does not give advice, the collection ultimately does, ending on two sonnets titled, “Advice for the Ghost Ship Jurors,” addressing the fire that broke out in an artists’ collective in Oakland in 2016 and killed 36 people. These final poems emphasize the jurors’ humanity in the face of mass, senseless tragedy. As readers trapped in my own small boxes, perhaps enduring forced silences of our own, these final poems serve as reminders that we are jurors of mass, mass tragedy. They urge us to expand. While this collection may resonate particularly well in our time of quarantine and a renewed social awareness of injustice, irreconcilable tragedies are a permanent feature of our lives, and McClung’s treatise with these poems is that we must not lose our humanity when we respond to them, and we must never descend into silence.

Learn more about McClung and her work here.

Written by Anna Winham