HOW TO POET

Holiday Gift Guide For Art-Lovers

As in-person shopping is now more difficult than ever, with the holiday upon us, it is easy to feel the avalanche of virtual advertisements. We are here to suggest some last-minute gift ideas for your art-lover friends and families.

With the holiday upon us, it is easy to feel the avalanche of virtual advertisements and decideophobia. Not to mention this year, in-person shopping has become more than difficult than ever. Thus, we are here to suggest some last-minute gift ideas for your art-lover friends and families.

Needless to say, 2020 has been a hectic year. We’ve witnessed the shut-down of some of our favourite local stores and our country at-large. Independent artists are struggling as galleries close, exhibitions keep getting canceled. The entertainment industry, at the same time, is also struggling to stay afloat. With these 7 little ideas, you are not only sending love to your giftees, but also supporting local artists!

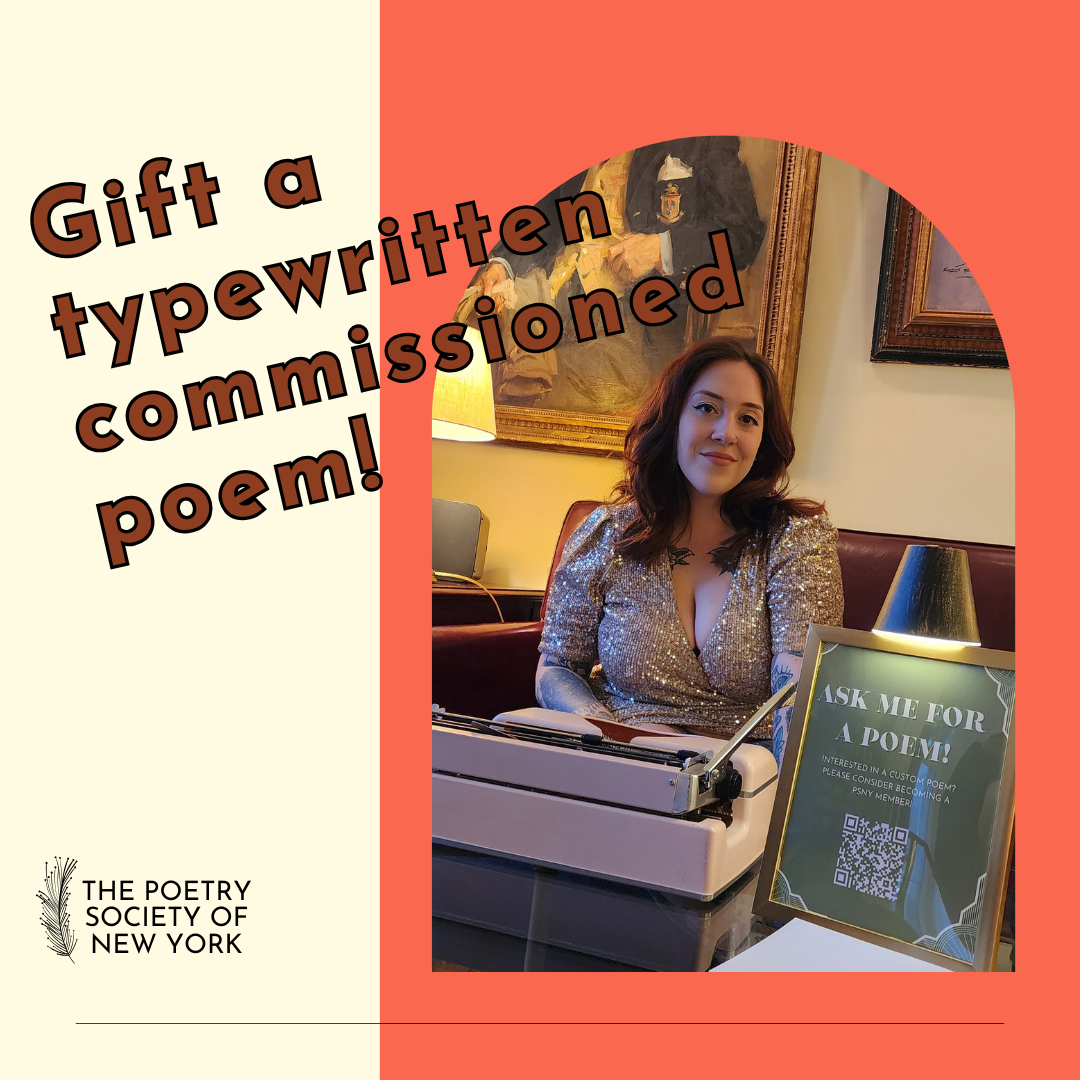

1. A Personalized Poem

Through the Poetry Society of New York, you are able to commission a personalized poem from one of the PSNY’s poets! Just share a few details about the person to whom you want to gift the poem, your relationship to them, some of your favourite memories, etc., and in less than a week, the poem will arrive in your friend’s mailbox!

2. The Poem Tote

In this New Yorker article, you are reminded of the golden rules on how to style your tote bag. The first and foremost thing: remember, totes are a great way to express yourself! That being said… Why not carry a poem tote that screams, Poems! ?

3. A Personalized Poetry Reading

On Poet Stream, you can connect to an international network of creators and receive from them a personalized reading. Surprise your beloved with a one-on-one zoom video with their favourite poets, or… tarot readers, pole dancers, guitar soloists, and 21 century witches!

4. Lady Poet T-shirt

If you are thinking of gifts for a poetry lover, then this series of lady poet T-shirts is your go-to gift. Featuring images of female poets including Anna Akhamatova, Lucille Clifton, Sylvia Plath, Audre Lorde, Adrienne Rich, Anne Sexton, etc., the Lady Poet Unisex T-shirt is also a part of the PSNY's Ideal Object series, a collab between PSNY's design team and a poet/artist who sought to manifest their vision of that object's formal ideal. You are also gifting the artists by purchasing, since 20% of each sale will be used to support the artist!

5. The Perfect Circle Pillow

Who wouldn't like something with poetry, art, and comfort all at the same time? The design of The Perfect Circle Pillow is inspired by the objects, activities, & places that brought us comfort during the pandemic. We promise it will create a more profound sense of comfort than your average pillow!

6. Milk Press Zine

A little zine is always a good idea. At Milk Press, there is a limited edition zine featuring works spontaneously created by the artists and poets who were at the 9th annual New York City Poetry Festival on Governors Island in 2019. This includes Chen Chen, Donna Masini, Armoni Boone, Tina Wang, Isabel Theselius, Sarahann Swain, Kate Belew, Heather Delaney, Larissa Hauck, Gregg Emery, and Nebula + Velvet Queen, etc. It will bring you and your friends back to the days where we could still hear live poetry in a split second.

7. PSNY Membership

If your friend/ lover/ family is a poetry lover who wants unique, one-of-a-kind experiences, why not gift them an annual membership at the Poetry Society of New York? The membership benefits include discounted tickets to the amazing Poetry Brothel performances, VIP admission to next year’s New York Poetry Festival, discounts for all merchandises, and so much more! Most importantly, they might just find their perfect poetry community.

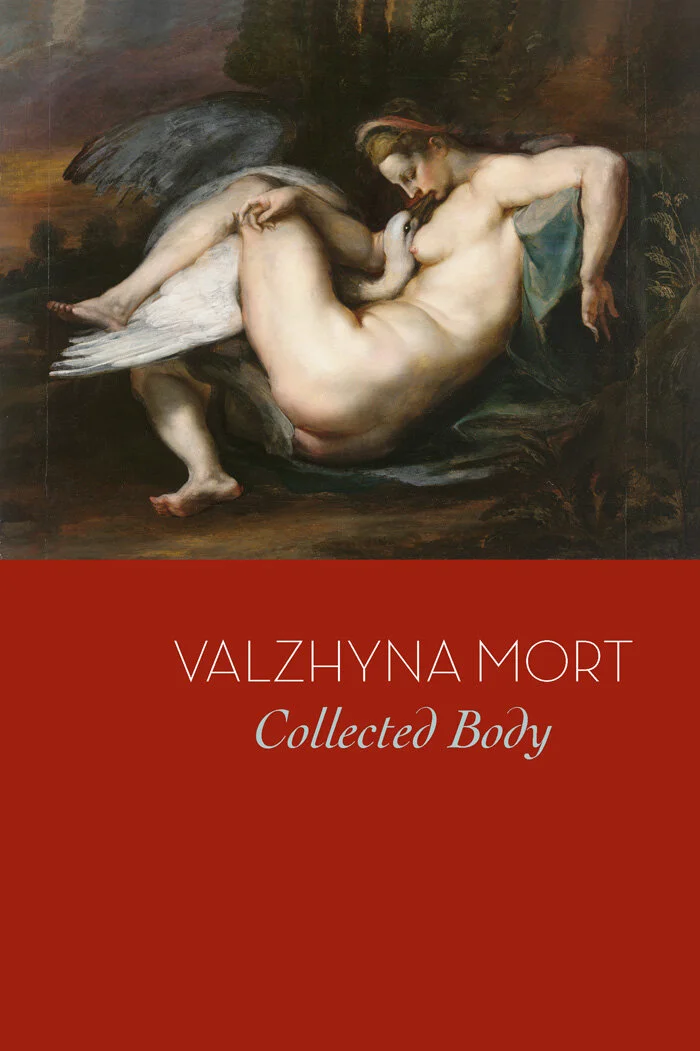

Clickbait Review: Valzhyna Mort's Collected Body

Belarusian poet Valzhyna Mort’s first collection written in English, Collected Body, is a complex tapestry of characters and their familial stories. In the collection, readers are constantly threatened by a sense of imminent death. Yet, instead of an end, death here becomes a means of union.

We at PSNY promise to publish only the most sincere book reviews and to only recommend products that we love. In the spirit of Clickbait, however, we want you to know that we will likely receive a portion of sales from products purchased through this article. Each click helps to support PSNY and Clickbait's writers directly, so we hope that you will use the links herein. Thank you for your support, dear readers!

Written by Yunqin Wang

Belarusian poet Valzhyna Mort’s first collection written in English, Collected Body, is a complex tapestry of characters and their familial stories. In the collection, readers are constantly threatened by a sense of imminent death. Yet, instead of an end, death here becomes a means of union.

Mort has placed her characters in their most vulnerable state, and at the same time let them fight off death in an extremely corporeal way. In Aunt Anna, the first prose poem of the book, Anna entered a childhood garden and “all she wanted to do was to eat” (28). In this way, “her belly couldn’t stop growing” (28). We are thus immediately introduced to the overarching metaphor between body and space, body and history in the collection. As Mort noted earlier in Aunt Anna that “A child...would learn that history had to be tangible like meat at dinner, but like meat at dinner, it also remained an abstraction” (19), we find the characters, in order to survive and to preserve their remaining relatives, try to fill up their physical bodies. It becomes their way to keep in contact with reality as well as history. In Zhenya, the second prose poem, the handicapped girl Zhenya moves from one place to another, yet gets lost. However, although lost in the physical world, she wishes for her body to extend — she “approaches that world…; reaches out for it… - insistently, aggressively, she knocks on the air, demands the air top open itself into something to walk through, to sit on, to lean against” (45). In the end, the swelling belly of Aunt Anna “became [her] younger brother”(28), and in the case of Zhenya, a classmate of the speaker, “we are finally pushed to reflect Zhenya in our own distorted ways.” (49)

The theme of reflection is not uncommon in the collection. To reconstruct each character’s personal history, Mort emphasizes how the characters are in relation with their intimate others. In Aunt Anna, for instance, thinking of her grandmother, the speaker feels “she bit [the teeth] through you, threaded a needle through the bites, and sewed you to that soil like a button….She threw over your head - a noose” (21). To assert her own existence, the speaker in Zhenya declares that her lover is “[her] plan for immortality”, “audience for [her] privacy” (49). In Island, “a road comes up to my face and stands like a mirror” (59). And at the end of Aunt Anna, Mort draws a surreal image which resembles the relationship of men to the world and to the dead, “... the building bared their hollowed heads and drained themselves into the eye sockets of the sleeping dead on the ground floors.” (25)

While death and memory are two main threads of the book, what makes Collected Body distinctive is how Mort tackles fearlessly taboo subjects, draws on raw physicality. Sylt I recounts an incest between an old father and four young sisters. However, the poem adopts neither an angry nor a harrowing tone. It is told calmly in an idyllic setting. The simile between body and food comes back. As the incest happens, “her teeth, crossed out by a blue line of lips, chatter, / scratching the grains of salt. Her bitter tongue / bleeds out into the mouth as red oyster, which she gulps, breathless.” The next stanza comes right in with the aftermath of the act, “Their father turns away to dry his cock” (7). Here, the violence, as a history desired to be erased, is expressed by the sister’s inability to digest. In contrast with Anna and Zhenya’s effort to enlarge their bodies, the girl feels “rough and indifferent toward her full breasts”. “It bothers her, what did he find there after all?” (7) Her body has become a shield crumbled, a vessel empty and evasive. Furthermore, the emotional distress of the speaker is expressed not through the description of her tormented flesh but the setting. “Sailboats slip off their white sarafans, / baring their scrawny necks and shoulders, / and line up holding on to the pier as if it were a dance bar.” (7) By stripping the subject of its horror, Mort has enabled us to look at the body and the story more clearly.

Just like her characters who resist to be erased from history, Mort also refuses to leave anyone out of her lyrics. The speaker whispers In Zhenya that “looking for Zhenya I find you” (49). In Aunt Anna, it is unavoidable to talk about Anna’s sister-in-law, young brother, husband, mother and children while the poem should be just about Anna. A new character is even introduced by the end of the poem. Mort writes, “A poem named after Aunt Anna, pages about Aunt Anna, and not one word about Boleska… (Boleska, if you are reading this, please find me, everybody is dead)” (32). The poet’s final attempt to refrain from the digression has failed, yet the introduction of Boleska is inescapable. It is both the result of the speaker’s wish to cling to her memories, and also because death ultimately united all.

Inevitably, all bodies decay in the end, yet Mort has seeked a way. In Love, located in a haunting apartment where “the neighbor is counting precious stones: / amiodarone, zofenopril, metoprolol, mexifin”, the speaker meditates, “Oh yes, she will inherit those jewels” (12). The jewel seems to be a hallmark that symbolizes the speaker’s awareness and acceptance of human mortality. By the end of the poem, the sweat of her lover “disperses, and multiples / like cockroaches” (13). Yet, remember the earlier stanza in the poem, “The spit shooting down the sink — / she still counts as his body. / The noose of his saliva over her pussy — / she still counts as his body… He folds her inside / and he ships her, and ships her, and ships…” (12) Mort, as well as all her characters, have given their stance before the unabashed acknowledgement of death: in this life journey, we should not leave anything, anyone out. And it’s with our bodies that we try to take in as much as we can.

Clickbait Review: Nathan Jurgenson's The Social Photo: On Photography and Social Media

By now it is no novel question to ask what the humanities owe the sciences, or indeed the sciences the humanities. The specture of the automaton is as old as the golem, which is to say as ancient as monotheism: this social anxiety regarding the essence of our humanity and its relationship to technology predates our modern conceptions of science. However, the meteoric rise in the social, political, and economic influence of technology companies such as Google, Apple, and Facebook demands that we continue reforming not only our answers to this question but our material responses to it. Social media theorist, editor emeritus of The New Inquiry, and sociologist at Snap Inc., Nathan Jurgenson addresses these disciplines via cyborg hybridity in his book The Social Photo: On Photography and Social Media.

We at PSNY promise to publish only the most sincere book reviews and to only recommend products that we love. In the spirit of Clickbait, however, we want you to know that we will likely receive a portion of sales from products purchased through this article. Each click helps to support PSNY and Clickbait's writers directly, so we hope that you will use the links herein. Thank you for your support, dear readers!

By now it is no novel question to ask what the humanities owe the sciences, or indeed the sciences the humanities. The specture of the automaton is as old as the golem, which is to say as ancient as monotheism: this social anxiety regarding the essence of our humanity and its relationship to technology predates our modern conceptions of science. However, the meteoric rise in the social, political, and economic influence of technology companies such as Google, Apple, and Facebook demands that we continue reforming not only our answers to this question but our material responses to it. Social media theorist, editor emeritus of The New Inquiry, and sociologist at Snap Inc., Nathan Jurgenson addresses these disciplines via cyborg hybridity in his book The Social Photo: On Photography and Social Media.

Written in 2.2 parts, The Social Photo is a brief but powerful exploration of the short history of photography, the even shorter history of social media, and the beginnings of their combination. The principle Jurgenson primarily returns to is historian Melvin Kranzberg's First Law of technology, which states: “Technology is neither good nor bad; nor is it neutral,” a refrain oft repeated by Jurgenson’s mentor Zeynep Tufekci in her influential Twitter and Tear Gas: The Power and Fragility of Networked Protest. Indeed, Jurgenson’s book marks the latest installment in a growing body of texts that urge us to, instead of rejecting technological advances, seek to take popular control of how they function.

Jurgenson rejects the “digital dualist dream behind so-called ‘cyber’ space and ‘virtual’ worlds,” arguing that our ‘true’ lives are not separate from the digital but infused with it. Our newfound obsession with “unplugging” to experience the somehow truer world “offline” stinks of digital influence: the heightened awareness of our lack of digital devices (and our obsession with then using those digital devices to announce our having been offline and what a Meaningful Experience™ it was via Twitter, magazine article, blog post, etc.) could only arise in the digital age, an age where the internet has extended beyond our devices and into our psychology. Just as photographers get “shutter eye” even when they are not carrying cameras, those of us who live in a world with social media begin seeing the world as Instagram-able, blog-able, record-able. Perhaps this renders the world consume-able in a way that seems unappealing, but is this so different from telling a story about our travels? Perhaps everything is (photo)copy after all.

The Social Photo is rife with references to the tensions inherent in photography between the ephemeral and the permanent, the copy and the original, the imitation and the authentic, the image and the world, what’s recorded and what’s outside the frame, indeed between the living with the dead. To take a photograph is to mediate upon mortality. The same has been said of writing poetry.

Over the course of photographic technology, the amount of time required to take, preserve, distribute a photograph has been decreasing to the point where it is now approaching zero, leading to dual impulses towards heightened permanence and heightened ephemerality. The craze circa 2010 of making digital photographs look like polaroids demonstrates this nostalgia for permanence and the hope that one’s digital photo might be imbued with the significance of an art object. This kind of social photo is demonstrated by more static interfaces such as the Instagram grid or a Facebook page. The impulse towards ephemerality works in the opposite way. Jurgenson develops an almost linguistic analysis of social photo use, stating that some social social photos such as jokes you might text to a friend, Snapchats, Instagram stories are designed to be snapped, viewed, and discarded, much like spoken language. This theory echoes linguist Gretchen McCulloch’s analysis of emoji and emoticon use as gesture in her book Because Internet. Images, particularly images of people, re-embody our discourse in the digital era. In the nineteenth century, reading novels was seen as scandalous: private, unhealthy, a distraction from conversation and more rigorous outdoor activities. Perhaps we should be no more concerned about our rapid escalation of image sharing than we now are about the proliferation of paperbacks.

Whatever our impulse in creating social photos--to record, to connect, to make art, to communicate--Jurgenson’s driving point in The Social Photo is that we live in a society and a social psychology which is now influenced by this kind of photography. Surely we, as a populace, would prefer to control the modes of production of the social photo than leave it up to large technology companies that profit off both our attention and our images? To some extent it seems like Jurgenson is putting his money where his mouth is--as a sociologist at Snap Inc. he surely seeks to influence the company in a leftist-populist direction--but any reader of Animal Farm knows, and I’d guess Jurgenson would agree, we should be suspicious of all who live in the farmer’s house and continue as a public to seek a truly democratic social landscape, both through the social photograph and otherwise.

Find more information about Jurgenson and his work here.

Written by Anna Winham

Clickbait Review: Kathleen McClung’s A Juror Must Fold in on Herself

The chapbook meditates on voice, how difficult it is to restrain our voices, how many of our voices are restrained by society.

We at PSNY promise to publish only the most sincere book reviews and to only recommend products that we love. In the spirit of Clickbait, however, we want you to know that we will likely receive a portion of sales from products purchased through this article. Each click helps to support PSNY and Clickbait's writers directly, so we hope that you will use the links herein. Thank you for your support, dear readers!

Kathleen McClung’s chapbook A Juror Must Fold in on Herself couldn’t have arrived at a better time for this sequestered reader, a juror in her own right. Several months into quarantine, interfacing with an unjust country from semi-permeable safety of my own solitude, I was turning in on myself, much like the sequestered juror of McClung’s bounded universe writing form poem after form poem. McClung writes in “Superior Court Ghazal,” “okay, so I may be over-/thinking here, but that’s what goes on in our little box.” At this point in time, who isn’t overthinking from her little box?

Some infinities are larger than others, but from where I’m sitting this still means that our small universes are infinite. If free verse is a large infinity, form poems are smaller ones. A villanelle, with its two repeating lines and strict rhyme scheme, seems restrictive, but the eternal lies here too. As poets know, no repetition is the identical. We cannot say the same thing twice. There is freedom to be found in restraint, and if we fold enough times we will soon be ten miles high.

This brief collection, restrained as it were, shifts voice poem by poem, from the District Attorney to the Public Defender to the Forewoman. Mostly we stick with the perspective of the Sequestered Juror, though, who figures in many forms: a rondeau, a pantoum, a sestina, a cento, a lament. She attempts time and again to order the tragedy at the centre of the book--what justice might be done about the death of a child--as though by organizing she might make sense of the senseless. We catch mere glimpses of the juror’s personhood; only small pieces of her life unfold: her mild attention to the “lanky prosecutor who doesn’t wear a ring,” her affection for her dog Alegria, her literary inclinations. We learn practically nothing of the defendant.

The chapbook meditates on voice, how difficult it is to restrain our voices, how many of our voices are restrained by society. From the very first poem, “Field Notes, Hall of Justice Parking Lot,” the juror longs to talk with the defendant but must not, for fear of being held in contempt of court. The Public Defender claims of the defendant, “his silence is his right” and later, “his silence is his choice,” though it does not seem like a choice. Meanwhile the Public Defender claims, “but me, I talk a lot,” and it’s unclear whether or not he is pleased with his own speech. An entire poem is composed of notes the juror does not write down; the poem is negative space, an absence, what could have been but was not, was held back. In the cento, she writes, “There are no words in our language to say this,” and yet what follows must certainly be the “this” she is saying. In the lament, speaking is one activity among a list of actions the jurors must not make. In the end, the juror prints her verdict on paper, and ultimately only the Forewoman speaks. At every point there is tension between silence and speech; a poem is never entirely one nor the other. A Juror Must Fold in on Herself builds the infinite into each small box.

All these meditations on silence, all these linguistic explorations of restraining the voice, all these foldings in on herself, open up into a sonnet crown ominously titled “Summons,” where the narrator seeks advice from her late grandmother, a courthouse stenographer, on how to conduct her legally imposed silence. Here it is the narrator who speaks, despite her enforced silence, while the grandmother, called on for advice, remains silent. Here we truly meet the narrator for the first time, see the fuller fabric of her life intertwined through her grandmother’s, and we see in parallel the humanization of the legal proceedings. The play of the title, the narrator invoking the presence of her dead ancestor and the court requiring one’s presence, emphasizes this entwining.

Though the grandmother does not give advice, the collection ultimately does, ending on two sonnets titled, “Advice for the Ghost Ship Jurors,” addressing the fire that broke out in an artists’ collective in Oakland in 2016 and killed 36 people. These final poems emphasize the jurors’ humanity in the face of mass, senseless tragedy. As readers trapped in my own small boxes, perhaps enduring forced silences of our own, these final poems serve as reminders that we are jurors of mass, mass tragedy. They urge us to expand. While this collection may resonate particularly well in our time of quarantine and a renewed social awareness of injustice, irreconcilable tragedies are a permanent feature of our lives, and McClung’s treatise with these poems is that we must not lose our humanity when we respond to them, and we must never descend into silence.

Learn more about McClung and her work here.

Written by Anna Winham

The Secret To Lying While Still Being American

Welcome to Open Sorcery - Clickbait’s open source collaborative poem-writing series. As we all know, poetry is magic. In the interest of creating some collective magic, we will be writing a new poem together each week using Google Docs!

Welcome to Open Sorcery

Clickbait’s open source collaborative poem-writing series.

As we all know, poetry is magic. In the interest of creating some collective magic, we will be writing a new poem together each week using Google Docs! If you would like to add to this week’s poem, please allow these rules:

Do not edit the existing text.

Do not make changes to the font or formatting of the document in any way.

Add no more than one line (-10 words) per entry and no more than 5 entries per day.

Do not use copyrighted material (unless you are licensed to use it).

Do not use hateful or bigoted rhetoric of any sort.

Please also note the following:

Please feel free to add stanza breaks or play with the space on the page, but please do not add full page breaks or create excessive space between your entry and others’.

The document updates automatically here on the site about every 2-3 minutes, so please do not expect to see your entry added in real time.

If you would like to submit a title for a future week’s poem, please do so here!

A note on publishing rights:

If your entry consists of your own original material or you own first rights to it, you will retain all rights to it and may use it at your sole discretion in perpetuity. By adding your entry, you authorize The Poetry Society of New York, Inc. to reproduce, publish, or otherwise copy your entry and to share it online, in print, or through any other communication medium without necessarily receiving credit or compensation. Given the anonymous, collaborative, and open source nature of this project, we thank you in advance for your understanding on this.

Access this week’s poem here to add your writing!

5 Creative Tips To Rock Your Virtual First Date

Orchestrating a successful first date during a global pandemic is tough. Ok — to do it really right is darn near IMPOSSIBLE. And when you add the fact that the only way to meet comfortably for many people is through computer screens - conducted through the vast ethereal space that is the internet - it’s easy to feel disconnected. Here are some fun ways to take your virtual first date to the next level, brought to you by The Poetry Society Of New York.

Orchestrating a successful first date during a global pandemic is tough. Ok — to do it really right is darn near IMPOSSIBLE. And when you add the fact that the only way to meet comfortably for many people is through computer screens - conducted through the vast ethereal space that is the internet - it’s easy to feel disconnected. It’s just plain hard to maintain the same kind of spark over a video call as you could during a night on the town.

But maybe things don’t need to be so bad. For better or worse, COVID-19 has pushed us into a new frontier of digital dating. And for all its downsides, there are new opportunities to infuse creativity and shake up the traditional dating model. And it may even be possible to do so without losing the cultural touch NYC dating deserves (even if you don’t happen to be in the Tri-State Area)!

Here are some fun ways to take your virtual first date to the next level, brought to you by The Poetry Society Of New York.

Invite a poet to help you break the ice!

Our Poet Stream service connects you with a network of poets, artists, tarot readers, mystics and more who perform in The Poetry Brothel, our international immersive theater experience. We can assure you that if you invite one of these artful characters to chaperone your date, they will instantly sense the mood and interchangeably intoxicate your soul and melt your heart.

Simultaneous evening cocktail and a movie!

Why not bring the classic romance of dinner theater to your living room? Make it a suit and tie affair. Or wear pajamas. Settle into your loveseat with some fresh popped popcorn and an Old Fashioned, then bravely drape an arm around the back of your laptop. Count back from three and simultaneously click to watch The Sound Of Music. Or something else is fine. Aren’t those von Trapp children just delightful! Or - wait - why didn’t Carol Baskin just let investigators DNA test her meat grinder??

Initiate a deep conversation.

If you’ve already established with each other in the initial Hinge chat that you are creative, complex and thoughtful people, double down and take the conversation a few levels deeper. Talk about visual art and its place in contemporary society, or the most important elements that constitute a good poem, or that new Cardi B music video and just how were they able to train all those snakes??

Seize the day: Go mobile!

Disconnect yourselves from those power chords and push the limits of your 4G network. Take your vid chat to-go on your cell phone, go out for a nature walk or stroll around your neighborhood and see what you both can discover. Find a cave in the woods (if you each have service) and recreate the chanting scene from Dead Poets Society. Oh captain, my captain!

Light a candle and share scary stories.

Nothing gets the blood pumping like a good horror story. Light a candle, cut the lights, and dive into the world of the grim and morbid. Or - if you’re not wanting to include fear as an element of your first date, scavenge through your house, locate the most ancient book you can find—the more tattered pages the better!—and recite a few passages to each other. Modern romance is steeped in nostalgia; tap that cultural reservoir of the ages and share something special!

I hope you enjoyed this semi-serious article, but Poet Stream is for real. Invite one of our poets to chaperone your next virtual date night for a one of a kind live arts experience!

The Cat Lifts Her Leg and Sees the First Leaf of Fall

Welcome to Open Sorcery - Clickbait’s open source collaborative poem-writing series. As we all know, poetry is magic. In the interest of creating some collective magic, we will be writing a new poem together each week using Google Docs!

Welcome to Open Sorcery

Clickbait’s open source collaborative poem-writing series.

As we all know, poetry is magic. In the interest of creating some collective magic, we will be writing a new poem together each week using Google Docs!

We Tasted Every Drop of Water in East River

Welcome to Open Sorcery - Clickbait’s open source collaborative poem-writing series. As we all know, poetry is magic. In the interest of creating some collective magic, we will be writing a new poem together each week using Google Docs!

Welcome to Open Sorcery

Clickbait’s open source collaborative poem-writing series.

As we all know, poetry is magic. In the interest of creating some collective magic, we will be writing a new poem together each week using Google Docs!

Why Trains Are Destroying America

Welcome to Open Sorcery - Clickbait’s open source collaborative poem-writing series. As we all know, poetry is magic. In the interest of creating some collective magic, we will be writing a new poem together each week using Google Docs!

Welcome to Open Sorcery

Clickbait’s open source collaborative poem-writing series.

As we all know, poetry is magic. In the interest of creating some collective magic, we will be writing a new poem together each week using Google Docs!

Some Bizarre Lamp Facts You Need to Know

Welcome to Open Sorcery - Clickbait’s open source collaborative poem-writing series. As we all know, poetry is magic. In the interest of creating some collective magic, we will be writing a new poem together each week using Google Docs!

Welcome to Open Sorcery

Clickbait’s open source collaborative poem-writing series.

As we all know, poetry is magic. In the interest of creating some collective magic, we will be writing a new poem together each week using Google Docs!

Guide To Write a Post-Apocalypse Postcard

Welcome to Open Sorcery - Clickbait’s open source collaborative poem-writing series. As we all know, poetry is magic. In the interest of creating some collective magic, we will be writing a new poem together each week using Google Docs!

Welcome to Open Sorcery

Clickbait’s open source collaborative poem-writing series.

As we all know, poetry is magic. In the interest of creating some collective magic, we will be writing a new poem together each week using Google Docs!

Emotion Dies Every Minute

Welcome to Open Sorcery - Clickbait’s open source collaborative poem-writing series. As we all know, poetry is magic. In the interest of creating some collective magic, we will be writing a new poem together each week using Google Docs!

Welcome to Open Sorcery

Clickbait’s open source collaborative poem-writing series.

As we all know, poetry is magic. In the interest of creating some collective magic, we will be writing a new poem together each week using Google Docs!

9 Reasons You Can Blame the Recession on Magic

Welcome to Open Sorcery - Clickbait’s open source collaborative poem-writing series. As we all know, poetry is magic. In the interest of creating some collective magic, we will be writing a new poem together each week using Google Docs!

Welcome to Open Sorcery

Clickbait’s open source collaborative poem-writing series.

As we all know, poetry is magic. In the interest of creating some collective magic, we will be writing a new poem together each week using Google Docs!

HOW TO QUIT YOUR DAY JOB AND FOCUS ON CONGRESS

Welcome to Open Sorcery - Clickbait’s open source collaborative poem-writing series. As we all know, poetry is magic. In the interest of creating some collective magic, we will be writing a new poem together each week using Google Docs!

Welcome to Open Sorcery

Clickbait’s open source collaborative poem-writing series.

As we all know, poetry is magic. In the interest of creating some collective magic, we will be writing a new poem together each week using Google Docs!

ASK YOUR DOCTOR WHAT MILLENNIALS REALLY THINK ABOUT SORCERY

Welcome to Open Sorcery - Clickbait’s open source collaborative poem-writing series. As we all know, poetry is magic. In the interest of creating some collective magic, we will be writing a new poem together each week using Google Docs!

Open Sorcery

Welcome to a new Clickbait series, Open Sorcery, an open source collaborative poem-writing series. As we all know, poetry is magic. We will be writing a new poem together each week in Google Docs in the interest of creating some collective magic! If you would like to add to this week’s poem, please follow these Open Sorcery commandments:

Thou shalt not edit the existing text.

Thou shalt not make changes to the font or formatting of the document in any way.

Thou shalt add no more than no more than one line (or 10 words) per entry and no more than 5 entries per day.

Though shalt break the line before adding your entry so that you leave the previous writer’s entry intact.

Though shalt not use copyrighted material (unless you are licensed to use it).

Though shalt not use hateful or bigoted rhetoric of any sort.

Please also note the following:

You may add stanza breaks or play with the space on the page, but please do not add full page breaks or create excessive space between your entry and others’.

The document updates automatically here on the site about every 2-3 minutes, so please do not expect to see your entry added in real time.

If you would like to submit a title for a future week’s poem, please do so here!

A note on publishing rights:

If your entry consists of your own original material or you own first rights to it, you will retain all rights to it and may use it at your sole discretion in perpetuity. By adding your entry, you authorize The Poetry Society of New York, Inc. to reproduce, publish, or otherwise copy your entry and to share it online, in print, or through any other communication medium without necessarily receiving credit or compensation. Given the anonymous, collaborative, and open source nature of this project, we thank you in advance for your understanding on this.

Relationships and Dating in the 21st Century

Call me cynical, but romance is a dead language. Dating in the 21st century makes me feel like an 80-year-old grandma stuck in the body of a 20- something. Is it just me or are your thumbs also too big for iPhone screens? My chubby fingers don’t belong in this intricate game of toss and catch.

By Teresa Mettela

Call me cynical, but romance is a dead language.

Dating in the 21st century makes me feel like an 80-year-old grandma stuck in the body of a 20- something. Is it just me or are your thumbs also too big for iPhone screens? My chubby fingers don’t belong in this intricate game of toss and catch. If you can’t package yourself in an aesthetically pleasing perfectly-punny Instagram bio, consider yourself hopeless like me. The hook. The bait. The trap. It’s all written in an invisible handbook when you download Tinder - you didn’t get the memo? We know our first lines. Our pitch. The move. It seems that everyone besides myself has given into the Hunger Games arena that is dating in 2020, but I’m not convinced.

Komal Kapoor, author of Unfollowing You, explores the messy business of “feelings” via social media.

“You have turned me into a cliche:

I check if you’re online

A dozen times a day

lol at your Snaps

{you’d be such an entertaining date}

and I wonder if you tweet about me

Or is there some other pizza-loving bae?”

Kapoor describes that itch we all have to check our social media a hundred times a day. It’s an addiction. A thirst. And it amplifies when we’re in love. Suddenly we’re calculating the perfect time to text back that special someone. We check our crushes’ Instagram, Facebook, and Twitter for updates and obsess over innuendos that probably weren’t even about us. It’s messy and exhilarating. Two extremes that somehow go perfectly together when under cupid’s bow and arrow.

Then, you’re dating.

“You created us

a Netflix profile

naming it our own

version of Brangelina.”

This is when social media becomes our best friend.

We think songs were made just for us. Facetime calls turn into virtual sleepovers. Netflix accounts were basically created for Friday night dates. You start watching shows together even though he’s the only person in the world who hasn’t seen The Office yet. Social media binds people in ways we don’t even realize.

That sinking feeling in the pit of your stomach when he leaves your text on read is all forgiven when the same someone drops heart emojis on your Instagram picture the next day.

Can love be born from a foundation of likes?

I still don’t know.

I fall victim to staring at my phone, waiting for those three little dots to appear. We can play hide and seek for hours on end. I clutch my device, making sure I feel it, shoved up against the fabric of my denim jeans - where it’s always been. I need to know the second someone texts me. Only to reply three hours later. It’s all for the feeling of control. We feign our authority for edgy personas and power moves. Social media gives me the one thing I always want more of: time. I can choose my words carefully. I can be a surgeon with her 10-blade. A painter with her brush. My fingers dance across the screen; they fall and fumble all the time, but you’d never know it.

We talk about how social media connects the masses. It serves as a vehicle for reunion and life. A renewal of friendships, love, and lust. Double-tap to like. You know the drill.

But what about the divide? Social media thrives on jealousy and miscommunication. Gossip spreads like wildfire and many of us get burned. We get canceled. Ghosted. Unfollowed.

“In moments of stillness

it is still your page I refresh.”

Now, here we are. Stuck at a crossroads. Can I text you? Will you text me? How many days are too many days without a “good morning” or “good night”? Of all the notifications popping up on my phone, I hope and pray that one of them is from you. In the days passing you archive our photos together, erasing our existence and I do the same. It’s a competition, isn’t it? I stop reaching for my phone, but the chill of its metal casing burns through my pockets. Avoiding you is impossible when you’re just a couple clicks away. I can’t help myself. You smile at me through my screen and I instinctively smile too.

I love you. I hate you.

“I no longer wonder

what it would be like

to build a life with you.

I can unfollow you now.”

*Sources: Poetry Foundation, Academy of American Poets, and back covers of the poets’ poetry collections are referred in the introductions above. Photos are from internet.

Kim Addonizio Waxes Poetic With Us

Jackie Braje of The Poetry Society of New York briefly chatted with Kim Addonizio before our Poet Parlor event about craft, advice for aspiring writers, and bodies on the earthly plane of existence.

Jackie Braje of The Poetry Society of New York briefly chatted with Kim Addonizio before our Poet Parlor event about craft, advice for aspiring writers, and bodies on the earthly plane of existence.

What subjects, ideas or themes have you been most drawn to while writing these days?

They’ve been pretty much the same my entire writing life. Love and death, suffering and our relationship to it. Life in a body on the earthly plane of existence. Something like that.

What does your relationship to your writing process look like? Do you have a specific and consistent practice?

I’m not very consistent these days. I’ve been trying to get back to a schedule. When I don’t read, I can’t write, and right now I’m having trouble concentrating in the middle of a pandemic and the end of the democratic American experiment.

Which writers or books have been the most sacred to you lately?

Right now, I’m listening more than reading. I’ve been falling asleep every night to Hilary Mantel’s last of the Cromwell trilogy. Love them all. I’ve been memorizing poems, something I hadn’t done for a while. Lately Yeats, Montale, and Millay. I’ve also got a chunk of the first section of Howl by heart. Memorizing does good things to your brain waves.

Who were your poetry mentors and how did they influence you?

I’ve never met my most important mentors. They’re mostly dead poets. I mean most of them are dead poets, not poets who are “mostly dead.”

What's one thing you'd like to try in a poem or a sequence of poems that you haven't tried before?

In my next book, Now We’re Getting Somewhere, coming out 2021, I have a poem that runs a dozen or so pages, with only one to four lines on a page. That felt like a real risk, but it just made sense. Someday I’d love to do a book of 14-liners. Sonnety things, but not necessarily strict sonnets. I’m very drawn to poems of that size.

Do you feel that there are certain parts of your identity that figure most strongly in your poetry?

The new book is very much a woman’s book. Both a performance, and maybe a critique, of female vulnerability. Along with the quotidian fucked-upness of the world.

What is your advice for aspiring writers?

Learn your craft, and care more about writing well than where you get published

Pride Began As a Protest: Remembering Marsha P. Johnson

As we moved into June, this year we are entering the Pride Month in a slightly different way. The country is amid the uprising over George Floyd’s death, racism, and violence. Yet, the spirit and the determination of the people remain the same. We are going through a transformative movement, just like how the LGBTQ patrons and community finally started to rebel on the night of June 28th, 1969. We should remember that our active voices and actions are needed in these moments, and the Pride celebration wouldn’t exist without protests.

As we moved into June, this year we are entering the Pride Month in a slightly different way. The country is amid the uprising over George Floyd’s death, racism, and violence. Yet, the spirit and the determination of the people remain the same. We are going through a transformative movement, just like how the LGBTQ patrons and community finally started to rebel on the night of June 28th, 1969. We should remember that our active voices and actions are needed in these moments, and the Pride celebration wouldn’t exist without protests.

The Stonewall Riots

June 28th, 1969 witnessed the occurrence of the Stonewall Riots in which the LGBTQ+ patrons and community fought back against police officers who had emptied out the Stonewall Inn, a communal space for the LGBTQ+ community in Greenwich Village, New York City, and abused a number of patrons. The riot soon led to protest marches and a more organized LGBTQ+ movement which sparked a new phase of the LGBTQ+ history. And Marsha P. Johnson, a Black trans woman native to New Jersey, an activist, a sex worker, a drag performer, has been an innegligible force in the uprising.

Marsha Pay-It-No-Mind Johnson

Marsha is remembered as one of the vanguards in the pushback against the police. In one account, a Stonewall veteren remembered Marsha "threw a shot glass at a mirror in the torched bar shouting, 'I got my civil rights'", and since that day, she has become an icon in the LGBTQ+ liberation history.

Marsha is the founding member of the Gay Liberation Front, and the co-founder of Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries (STAR), one of the country's first safe spaces for transgender and homeless youth. She also tirelessly fought for people with HIV/AIDS between From 1987 through 1992 with ACT UP. She was known as the “mayor of Christopher Street”, always on the front lines of the LGBTQ+ liberation movement. And when asked what the “P” in her name stood for, she answered, “Pay it no mind”. Marsha Pay-It-No-Mind Johnson.

Unresolved Death

Marsha died in 1992 at age 46. Her body was found in the Hudson River, after reported missing, and her death was ruled by the police a suicide, which members of the local gay community disputed. In 2012, authorities reopened the case and reclassified the cause of death as undetermined. The case still remains open today.

Marsha’s mysterious death seems to remind all of us -- it is not over. There is still ongoing violence towards the minority communities, and people are still living in anger, fear, and frustration. The case, remaining unclosed, as if proclaims that Marsha will be the ultimate survivor, with her spirit passed on and her message always heard and acted upon: the fight should go on. Al Michaela, Marsha’s nephew, said in an interview that if Marsha were here today, he believed she’d still be pushing, that "we want 100% of our rights that everybody else gets and until we get that, the fight continues."

What We Could Do

PSNY has collected a list of resources for supporting the transgender community, sex workers during this time of COVID-19.

Cora Colt and Ceyenne Doroshow, founder of our partner organization Gays and Lesbians in a Transgender Society (GLITS) are organzing this campaign in behalf of Twinkle Paule, a transgender activist, migrated from Guyana to the States, to raise funds and provide needed services to Trans SWs in Guyana.

In addition, for the past few months, Doroshow and her organization GLITS has been providing housing in NYC for five black trans people recently released from Riker’s Island. They have an opportunity to sign a lease on an apartment to provide much needed security and housing stability for these people.

The Sex Workers Outreach Project in Brooklyn has started the campaign To provide monetary aid to sex workers in the New York City area who have been impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic.

#BlackLivesMatter: Guide to 6 Black Poets Who Have Given Me Strength

In one of the essays of Joseph Brodsky, he declared that at certain periods of history, it might be only poetry that is capable of dealing with reality by condensing it into something graspable, something that otherwise couldn't be retained by the mind. In a moment like this, when sounds of sirens, voices for justice, cries of victims drum in our ears all at once, I believe alongside donating and speaking up, another thing we could do is to understand…

Written by Yunqin Wang

In one of the essays of Joseph Brodsky, he declared that at certain periods of history, it might be only poetry that is capable of dealing with reality by condensing it into something graspable, something that otherwise couldn't be retained by the mind. In a moment like this, when sounds of sirens, voices for justice, cries of victims drum in our ears all at once, I believe alongside donating and speaking up, another thing we could do is to understand. To understand what is happening and the people being involved. We do not want to be suffocated together in this air of bias, violence and intolerance. And these poets, clinging to their pens and sheaves of paper all along, have been paving a long road for this understanding to happen.

In this article, I’m sharing with you some of the black poets who have moved me deeply. Their influence over not just the literary realm but also the entire human history has proclaimed over and over: black lives matter.

Lucille

Clifton

“won’t you celebrate with me” by Lucille Clifton is one of the earliest poems I have ever read in my life, and it then became a poem that supported me during some of my most difficult times. Clifton, who has experienced segregation and racism firsthand, has offered me with this poem a guide to self-understanding.

Born in Depew, New York, Lucille Clifton was the first author to have two books of poetry chosen as finalists for the Pulitzer Prize and the winner of Ruth Lilly Poetry Prize, whose judges marvelled at the looming humaneness and moral quality in her works. Many of her poems, including “won’t you celebrate with me” were written in the 1960s. It was a time when the civil rights movement awakened a new sense of self-awareness of African Americans. As part of this generation of whom had experienced both an historical exile from Africa and a metaphorical exile from the so-called American Dream, Clifton has always sought in her poetry to position herself and her people in relation to the world. Her works emphasized endurance and strength through adversity.

In this short poem “won’t you celebrate with me”, as the narration goes, the speaker gathers more and more strength from her own experience, more confidence from her ability to stand alone. It investigates reasons for the faltering sense of identity and then overcomes it, thus giving me strength too.

won't you celebrate with me

what i have shaped into

a kind of life? i had no model.

born in babylon

both nonwhite and woman

what did i see to be except myself?

i made it up

here on this bridge between

starshine and clay,

my one hand holding tight

my other hand; come celebrate

with me that everyday

something has tried to kill me

and has failed.

Gwendolyn Brooks

I was introduced to Gwendolyn Brooks in my first creative writing class in college. The poem we read was “The Sundays of Satin-Legs Smith”, the longest poem in Brooks’ first collection, “A Street in Bronzeville”. I was immediately attracted to the poet’s elaborative language which weaves the character’s inner-self and the awareness of the outside world so well -- there is irony, and also beauty. That is Gwendolyn Brooks, she is always clear about who the people she wrote were and what it meant to write about them. And for most of her works, even though her creative style went through different phrases--from tighter to more loosened with less dense allusions--her subject matter has remained unchanged: she looks at the black people who lived in the kitchenette apartments of Bronzille.

One of the most highly regarded poets of 20th-century American poetry, Brooks was the first Black author to win the Pulitzer Prize, and also the first Black woman to be assigned the poetry consultant to the Library of Congress. Distilling a modernist style through the unique sounds and shapes of a variety of African-American forms and idioms, her works, especially those from the 1960s and later, often display a political consciousness too. I am moved by the unambiguous race pride penetrating through her words which, after so many years, still ring true to the complex poetic details of black people’s lives.

This poem below is from the collection, “A Street in Bronzeville”. Starting with the pronoun “we”, the poem immediately brings out a crowded yet lonely voice of this community living in these close quarters.

kitchenette building

We are things of dry hours and the involuntary plan,

Grayed in, and gray. “Dream” makes a giddy sound, not strong

Like “rent,” “feeding a wife,” “satisfying a man.”

But could a dream send up through onion fumes

Its white and violet, fight with fried potatoes

And yesterday’s garbage ripening in the hall,

Flutter, or sing an aria down these rooms

Even if we were willing to let it in,

Had time to warm it, keep it very clean,

Anticipate a message, let it begin?

We wonder. But not well! not for a minute!

Since Number Five is out of the bathroom now,

We think of lukewarm water, hope to get in it.

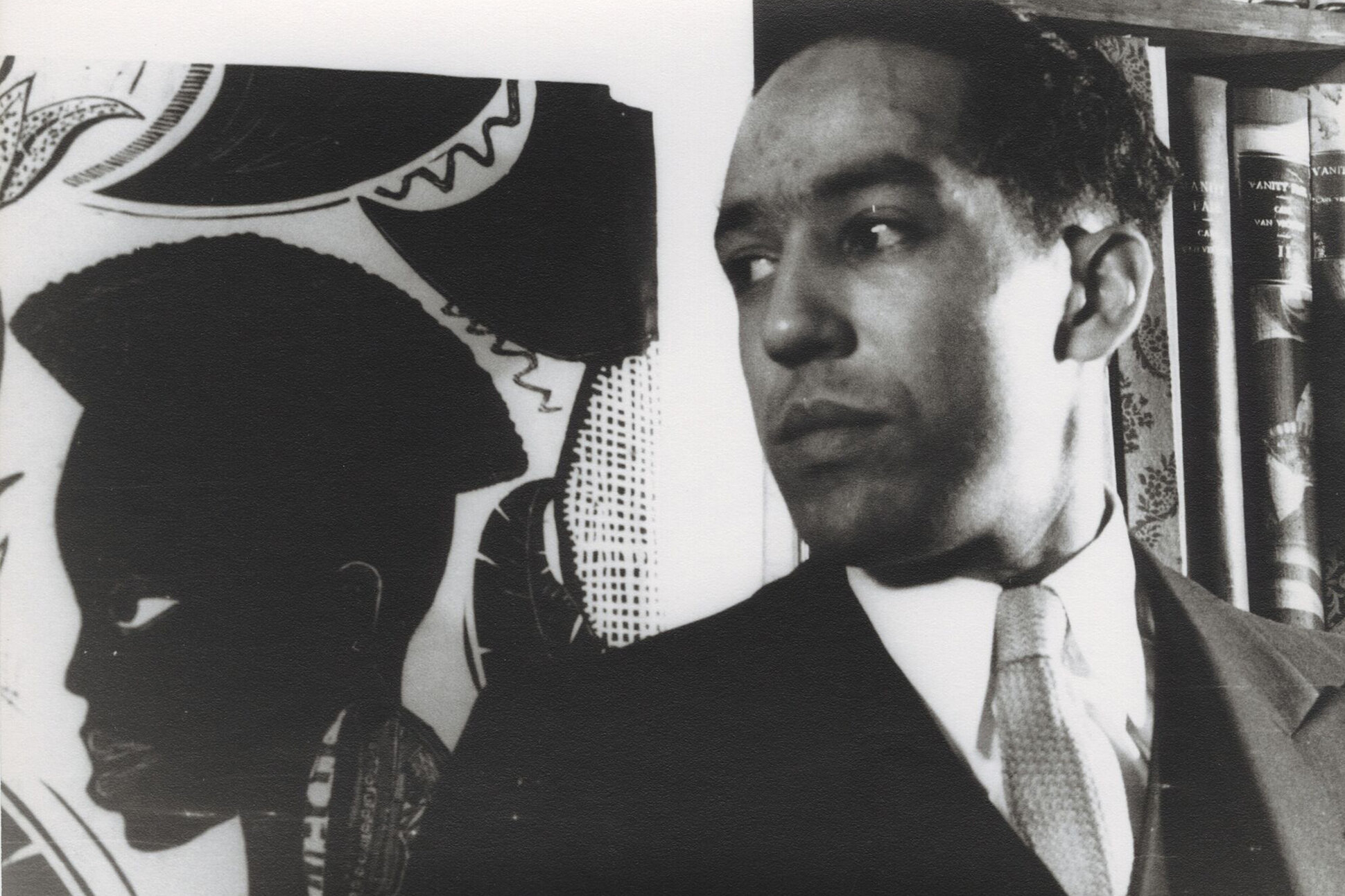

Langston Hughes

Langston Hughes, has been one of the early and enduring influences of Brooks. The conversational and syncopated rhythms, people and personalities, as well as urban settings in Brooks’ works to some degrees owe to Hughes’ influences. And Langston Hughes, a major poet and a central figure of the Harlem Renaissance--the flowering of black intellectual, literary, and artistic life that took place in the 1920s in a number of American cities--could be regarded almost as influential an anthologist as he was a poet. Portraying the joys and hardships of working-class black lives yet avoiding both sentimental idealization and negative stereotypes, Hughes’ works have for several generations of readers helped form a sense of an American poetics and the possibilities of African American literature. Through his words, we not only witness moments of race-pride, but also feel a strong sense of urgency, an urgent revelation and belief. Helen Vendler has once commented that perhaps, in this man’s hurried life, “he may have believed the cause was so urgent that it did not leave him the time for that digestion of thought into style that alone allows poetically successful representation of belief.”

Harlem Renaissance

In this piece below, Hughes, adopting a Whitman-style voice performed yet what Whitman could not achieve: he imagines a truly equal place at the table for “the darker brother.” It sings to me how beautiful the black experience is.

I, Too

I, too, sing America.

I am the darker brother.

They send me to eat in the kitchen

When company comes,

But I laugh,

And eat well,

And grow strong.

Tomorrow,

I’ll be at the table

When company comes.

Nobody’ll dare

Say to me,

“Eat in the kitchen,”

Then.

Besides,

They’ll see how beautiful I am

And be ashamed—

I, too, am America.

Maya Angelou

I believe most of us are familiar with Maya Angelou, but she is indeed the figure who should be brought up again at this time. She had a broad and distinguished career not only inside but also outside the literary realm. She is a poet, memoirist, and civil rights activist, working with Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X. She also worked in entertainment, as a singer, a dancer, an actor, and a director. Inspired by her own life and work, also with a firm root in African American history, the poetry of Maya Angelou bears both deep personal connections and the strength to bring out hopes, calling us to overcome any kinds of oppressions. The power of rhythm in Angelou’s verse also indicates her belief that life struggles could be overcome through rhymes and our voices. When she was eight, she was raped by her mother’s boyfriend who was killed shortly after. She thought her voice had killed the man and remained mute for five years, but developed a love for language. After all, she knows the great force of both oppression and voice, both silence and words.

Over the course of a career spanning the 1960s to her death in 2014, Angelou captured, provoked, inspired, and ultimately transformed American people and culture. By 1975, Carol E. Neubauer in Southern Women Writers: The New Generation remarked that Angelou should be recognized “as a spokesperson for… all people who are committed to raising the moral standards of living in the United States.” The poem below, written at the time of Black Arts Movement, is indeed calling every one of us in this society to rise, and live above the society.

Still I Rise

You may write me down in history

With your bitter, twisted lies,

You may trod me in the very dirt

But still, like dust, I'll rise.

Does my sassiness upset you?

Why are you beset with gloom?

’Cause I walk like I've got oil wells

Pumping in my living room.

Just like moons and like suns,

With the certainty of tides,

Just like hopes springing high,

Still I'll rise.

Did you want to see me broken?

Bowed head and lowered eyes?

Shoulders falling down like teardrops,

Weakened by my soulful cries?

Does my haughtiness offend you?

Don't you take it awful hard

’Cause I laugh like I've got gold mines

Diggin’ in my own backyard.

You may shoot me with your words,

You may cut me with your eyes,

You may kill me with your hatefulness,

But still, like air, I’ll rise.

Does my sexiness upset you?

Does it come as a surprise

That I dance like I've got diamonds

At the meeting of my thighs?

Out of the huts of history’s shame

I rise

Up from a past that’s rooted in pain

I rise

I'm a black ocean, leaping and wide,

Welling and swelling I bear in the tide.

Leaving behind nights of terror and fear

I rise

Into a daybreak that’s wondrously clear

I rise

Bringing the gifts that my ancestors gave,

I am the dream and the hope of the slave.

I rise

I rise

I rise.

Yusef

Komunyakaa

Last night, I put down the poetry collection Dien Cai Dau by Yusef Komunyakaa, feeling like I just had a long dream. It is a collection of poems on the poet’s experience as a soldier at the Vietnam War. Loss, struggle, fear, relations between black and white soldiers, humanity of the enemy… All kinds of emotions flow in this book, in between the harrowing lines.

On April 29, 1947, Yusef Komunyakaa was born in Bogalusa, Louisiana where he was raised during the beginning of the Civil Rights movement. From 1969 to 1970, he served in Vietnam as a correspondent and managing editor for the military newspaper Southern Cross, work that earned him a Bronze Star. Yet it was only in 1984, 14 years after he returned home, did he start to reflect on his experience in the war fields, and we thus have in hand the collection Dien Cai Dau, which means “crazy” in Vietnamnese. I think there must be certain intersections between how Komunyakka in his book reminds us of the struggles of those suffered, mistreated, even forgotten in the war and how today in the Black Lives Matter movements people once again actively start to voice out, listen, empathize. Komunyakka recounted the war experience in a distant yet almost ghostly voice. He is here dealing with some of the most complex moral issues, writing about the most harrowing ugly subjects of the American life, and yet, as the poet Toi Derricotte remarks, his voice, whether it embodies the specific experiences of a black man, a soldier in Vietnam, or a child in Bogalusa, is universal. And through this African American veteran, I have learned, deeply, what it is to be human.

Vietnam Veterans Memorial Wall

“Facing it” is the ending poem of the collection, though one of the first poems Komunyakka started out to write about the war 14 years later. Standing before the Vietnam Wall, he confronts his feeling for that history. And while reading I think, we should never turn our nation into a place which doesn’t recognize its own soldiers.

Facing it

My black face fades,

hiding inside the black granite.

I said I wouldn't

dammit: No tears.

I'm stone. I'm flesh.

My clouded reflection eyes me

like a bird of prey, the profile of night

slanted against morning. I turn

this way—the stone lets me go.

I turn that way—I'm inside

the Vietnam Veterans Memorial

again, depending on the light

to make a difference.

I go down the 58,022 names,

half-expecting to find

my own in letters like smoke.

I touch the name Andrew Johnson;

I see the booby trap's white flash.

Names shimmer on a woman's blouse

but when she walks away

the names stay on the wall.

Brushstrokes flash, a red bird's

wings cutting across my stare.

The sky. A plane in the sky.

A white vet's image floats

closer to me, then his pale eyes

look through mine. I'm a window.

He's lost his right arm

inside the stone. In the black mirror

a woman’s trying to erase names:

No, she's brushing a boy's hair.

June Jordan

In an episode of the “Poetry Off the Shelf” podcast, the host tried to introduce June Jordan but failed to categorize her. He said, “But let’s try. [She is] An African-American bisexual political activist, writer, poet, and teacher. But if you try to look at her through that lens, you will not see all of her.” Toni Morrison, on June Jordan’s career, remarked, "I am talking about a span of forty years of tireless activism coupled with and fueled by flawless art." Back in the 1960s, Jordan was one of the first writers to validate African American vernacular. And I wonder, what would Jordan, who had committed full heartedly to human rights and political activism throughout her life, make of the incidents we are facing today.

Born in Harlem in 1936 to Jamaican immigrant parents, she is a poet who was fiercely connected to and living in this world. She was so conscious and aware of what was going on politically, and more importantly, had the ability to bring that out into her work. We are constantly challenged by her words, being pulled out to confront this world. In a radio interview before her death, Jordan was asked about her role as a poet in the society. Here is part of the answer, “...the task of a poet of color, a black poet, as a people hated and despised, is to rally the spirit of your folks…I have to get myself together and figure out an angle, a perspective, that is an offering, that other folks can use to pick themselves up, to rally and to continue or, even better, to jump higher, to reach more extensively in solidarity with even more varieties of people to accomplish something. I feel that it’s a spirit task.”

While Jordan has left us physically, the power of her work stays real, transformative, transcending time. To end this article, I will include one of her last poems before cancer took her away. Jordan asks over and over In this poem, “what’s anyone of us to do / about what’s done” and answers through her action both inside and outside the poem. She is sending the message that the effort to do it, regardless of the degree of restoration, is hard but necessary like a laundry, and beautiful. This spirit of bettering the world through art and activism, let us pass it on.

It’s Hard to Keep a Clean Shirt Clean

Poem for Sriram Shamasunder

And All of Poetry for the People

It’s a sunlit morning

with jasmine blooming

easily

and a drove of robin redbreasts

diving into the ivy covering

what used to be

a backyard fence

or doves shoving aside

the birch tree leaves

when

a young man walks among

the flowers

to my doorway

where he knocks

then stands still

brilliant in a clean white shirt

He lifts a soft fist

to that door

and knocks again

He’s come to say this

was or that

was

not

and what’s

anyone of us to do

about what’s done

what’s past

but prickling salt to sting

our eyes

What’s anyone of us to do

about what’s done

And 7-month-old Bingo

puppy leaps

and hits

that clean white shirt

with muddy paw

prints here

and here and there

And what’s anyone of us to do

about what’s done

I say I’ll wash the shirt

no problem

two times through

the delicate blue cycle

of an old machine

the shirt spins in the soapy

suds and spins in rinse

and spins

and spins out dry

not clean

still marked by accidents

by energy of whatever serious or trifling cause

the shirt stays dirty

from that puppy’s paws

I take that fine white shirt

from India

the threads as soft as baby

fingers weaving them

together

and I wash that shirt

between

between the knuckles of my own

two hands

I scrub and rub that shirt

to take the dirty

markings

out

At the pocket

and around the shoulder seam

and on both sleeves

the dirt the paw

prints tantalize my soap

my water my sweat

equity

invested in the restoration

of a clean white shirt

And on the eleventh try

I see no more

no anything unfortunate

no dirt

I hold the limp fine

cloth

between the faucet stream

of water as transparent

as a wish the moon stayed out

all day

How small it has become!

That clean white shirt!

How delicate!

How slight!

How like a soft fist knocking on my door!

And now I hang the shirt

to dry

as slowly as it needs

the air

to work its way

with everything

It’s clean.

A clean white shirt

nobody wanted to spoil

or soil

that shirt

much cleaner now but also

not the same

as the first before that shirt

got hit got hurt

not perfect

anymore

just beautiful

a clean white shirt

It’s hard to keep a clean shirt clean.

*Sources: Poetry Foundation, Academy of American Poets, and back covers of the poets’ poetry collections are referred in the introductions above. Photos are from internet.

Try This Rain Meditation For Spring Showers

When I think of New York, I think of rain. It’s chasing a year since I spent time in the city working at The New York City Poetry Festival and still my freshest memories are of falling water. I can smell the dank subway on my way home from Central Park’s deep puddles; from a deli doorway on a quiet street I watched the city sink.

By Lucy Cheseldine

When I think of New York, I think of rain. It’s chasing a year since I spent time in the city working at The New York City Poetry Festival and still my freshest memories are of falling water. I can smell the dank subway on my way home from Central Park’s deep puddles; from a deli doorway on a quiet street I watched the city sink. Rain feels right in isolation. It isolates. It pushes us inside and keeps us in rooms with its sudden showers. Or it sets us to daily tasks with taps that sound out the rhythm of steady work. Rain is homemaker and caretaker. It prompts conversation. I remember speaking with a doorman who recommended over and over his mother’s Cajun cooking as if, when the rain stopped, we might celebrate together with dinner. Rain is ceremony and birth: it washes out and cleans corners. To rain we open our mouths in the hope of its blessing, forming words as we go. But rain silences too with its war-like pelting, scattering the city to shelter. Rain leaves no people out, showering without discrimination, but it shows who we’ve left out from the safety of high windows by soaking the discriminated. It can be an angry divinity. Rain is like lock down; rain is like illness; rain is like life. Rain is Spring’s never timelier gift.

It’s little wonder that so many poets have taken rain as their subject. In Elizabeth Bishop’s “Song for a Rainy Season”, rain is a collector of images to “the ordinary brown/owl” and “fat frogs”. Its drops of water domesticate and summon a democracy of the forest:

House, open house

to the white dewa

nd the milk-white sunrise

kind to the eyes,

to membership

of silver fish, mouse,

bookworms,

big moths; with a wall

for the mildew's

ignorant map;

This house, “beneath the magnetic rock/rain,/rainbow-ridden”, opens onto the world. Her quaint lyric is “rainy”, harmless and intermittent, and its various intruders are most welcome. But only for a time, “For later/era will differ”. The world will move one, leaving us behind, “no longer wearing rainbows or rain” as “waterfalls shrivel/in the steady sun”. Our place here is temporary. Today, in our closed houses, such knowledge feels close. For Bishop too, knowledge is like water. As she tells us is in “At The Fishouses” it is “historical, flowing, flown”. Rain and its element can make a slippery case for existence.

For Wallace Stevens rain is also a passing in his poem “Sunday Morning”:

Passions of rain, or moods in falling snow;

Grievings in loneliness, or unsubdued

Elations when the forest blooms; gusty

Emotions on wet roads on autumn nights;

All pleasures and all pains, remembering

The bough of summer and the winter branch.

These are the measures destined for her soul.

Unlike Bishop’s porous house, there’s an integrity to Stevens’s “passions”. Rain is a necessary release, pulling our internal life towards lived experience. It’s hard to find these moments confined to the high-rise flats and human tracks we’ve made of our cities. But perhaps now is as good a time as any to ask how we’ve been measuring what’s “destined for” our souls. Another comfort I take from this poem, at a time of potential boredom, is the unstoppable nature of human drama. While these fits of feeling can be trying and difficult, I think Stevens knew too that in another sense our inner life provides the most constant and vital form of activity, even entertainment. Much like the rain. Or as William Carols Williams writes “so much depends/upon/a red wheel barrow/glazed with rain water”. Like his language, so much depends on our material banalities being a passage to grasping what we can’t touch.

During the pandemic, as I sit inside watching the world through drips and drops, I have the uncanny feeling that instead the world is watching me. The empty streets ask questions and the trees want answers. Or they don’t. Their vacant stares are I-told-you-so. At a time of uncertainty and vigilance, I turn to Philip Larkin’s “The Whitsun Weddings” to think about what we need to leave behind, who we should watch out for with greater care, and who we should stop watching. His rain is elsewhere but it is going to fall, and when it does, the hope is change:

They watched the landscape, sitting side by side

—An Odeon went past, a cooling tower,

And someone running up to bowl—and none

Thought of the others they would never meet

Or how their lives would all contain this hour.

I thought of London spread out in the sun,

Its postal districts packed like squares of wheat:

There we were aimed. And as we raced across

Bright knots of rail

Past standing Pullmans, walls of blackened moss

Came close, and it was nearly done, this frail

Travelling coincidence; and what it held

Stood ready to be loosed with all the power

That being changed can give. We slowed again,

And as the tightened brakes took hold, there swelled

A sense of falling, like an arrow-shower

Sent out of sight, somewhere becoming rain.

Calling all young poets, artists, and entrepreneurs! Showcase your creativity and sell your work at one of NYC’s most exciting cultural events—the New York City Poetry Festival on Governors Island! This is your chance to connect with fellow artists, poetry lovers, and a vibrant community ready to support young creators like you.

🌟 What You Get:

✅ Sell & Share Your Work – Whether it’s poetry chapbooks, art, handmade goods, or creative services, you have full permission to sell and promote your creations at the festival.

✅ Your Own Vendor Space – A shared table setup in our Youth Vendor Village! Each vendor gets dedicated space at a 6-foot table and two chairs.

✅ Be Part of the Festival Energy – Immerse yourself in a weekend of poetry, performance, and connection with a creative community that values youth voices.

💡 Important Details:

For Ages 18 & Under – This special rate is designed to support young creators looking to share their work with the world.

Non-Refundable – All vendor package purchases are final, so plan ahead!

Limited Spots Available – Secure yours early to guarantee your space!

🎤 Why Join?

✨ Visibility & Connection – Get your work in front of an engaged audience who appreciates creative expression.

✨ Supportive Community – Be part of an event that fosters youth creativity and artistic growth.

✨ Affordable & Accessible – At just $20, this is an amazing opportunity to gain real-world vendor experience without a big investment.

🚀 Reserve Your Spot Today! Spaces are limited, so sign up now and be part of NYC’s thriving poetry scene!